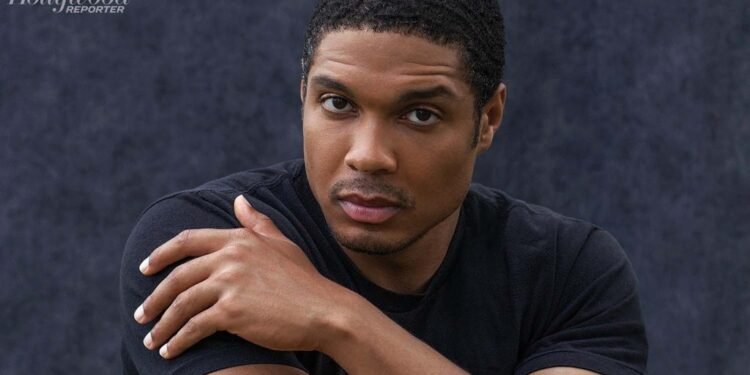

Over the past year, the actor has assailed the filmmaker and studio in harsh-but-cryptic tweets for what he says was racist and inappropriate conduct: “I’m not so indebted to Hollywood that I haven’t been willing to put myself out there.”

Ray Fisher is ready to talk.

Ever since June 2020, when he fired off a tweet accusing Joss Whedon of “gross, abusive, unprofessional, and completely unacceptable” conduct on the set of Justice League, the 33-year-old actor has used social media and a series of interviews to lob serious allegations of racist behavior and a cover-up at Warner Bros.

For Fisher, who plays Cyborg in the film, the issue is no longer so much what happened on the set in 2017, after director Zack Snyder was replaced by Joss Whedon, though he’s ready to explain that, too. His unrelenting focus in recent months has been the way executives, first at the Warner film studio and then at its parent, WarnerMedia, handled allegations raised by himself and others.

WarnerMedia has previously said that “remedial action” was taken as a result of its investigation but has not elaborated. A spokesperson tells THR that for privacy and legal reasons, “our policy is to not publicly disclose the findings or the results of an investigation.”

Katherine Forrest, a former federal judge who conducted the WarnerMedia probe, tells THR in a statement that in interviews with more than 80 witnesses, she found “no credible support for claims of racial animus” or racial “insensitivity.” A WarnerMedia spokesperson notes that the company “made extraordinary effort to accommodate Mr. Fisher’s concerns about the investigation and to ensure its fullness and fairness” and has “complete confidence in the investigation process and [Forrest’s] conclusions.”

Fisher was raised by a single mother and his grandmother in Lawnside, New Jersey — a community that he notes was the first self-governing Black municipality north of the Mason-Dixon Line. He says he felt a new sense of urgency to speak out when the pandemic hit and the Black Lives Matter protesters took to the streets.

To Fisher, who had few screen credits, playing the half-man, half-machine Cyborg — the first Black superhero in the DC film universe — was both a huge career break and a major responsibility. (Justice League was released in 2017, the year before Marvel broke ground with Black Panther.) He was mindful that the film was overseen almost entirely by white executives and filmmakers.

While Fisher has dropped details and named names, outsiders have struggled to understand: How did Whedon incur his anger? Did Fisher really decline to participate in an investigation that was launched in response to his own complaints, as Warners claimed in September? Was Fisher fighting a righteous battle or a quixotic one when he set out on a path that appears to have cost him a place in the DC film universe?

Now, in many hours of conversation, Fisher tells his side. Much of his previous reluctance to spell out the story, he says, arose because he didn’t — and still doesn’t — want to expose the identities of others who shared their stories with him and investigators. “I’m not looking to have any witnesses lose their jobs,” he says.

Those include some who wouldn’t seem to have any worries about job security: Gal Gadot and Jason Momoa. Others who were not involved with Justice League also spoke to Fisher and in some cases the investigators about experiences with Whedon and with Geoff Johns, who was co-chairman of DC Films and a producer on the film. They include Charisma Carpenter, who recently wrote on social media of Whedon’s alleged abusiveness on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and individuals who had worked with Johns on Syfy’s Krypton.

Fisher got Warners to start an investigation, more than two years after the first version of the film was released. But he soon found the process to be suspicious. The studio and its parent company seemed to be focused on protecting top executives, he says. The process moved in starts and stops, and when he felt forced to ramp up his public protest, the studio responded with what Fisher calls a deliberate smear. Warners maintains it has done everything necessary to address Fisher’s concerns. He still wants an apology.

***

In May 2017, Fisher was walking into a movie in New York when he got a call from Zack Snyder that left him stunned: Snyder was leaving Justice League, citing his daughter’s suicide. Sources say Snyder was under enormous pressure at the time. The studio was unhappy with the reception and box office performance of his previous film, the bleak Batman v. Superman, and — with Justice League footage already shot — now insisted on a lighter touch. Warners also asked Snyder to produce a two-hour cut that he had a wrenching time delivering, though eventually did. Ultimately Snyder left, and Whedon — who had written and directed Marvel’s The Avengers and had already been brought in to help brighten Justice League‘s tone — took the helm.

The Justice League that Fisher had signed up for was a far cry from the film that Whedon ended up finishing. Snyder had Fisher talk at length with screenwriter Chris Terrio before there was even a script. “Zack and I always considered Cyborg’s story to be the heart of the movie,” Terrio tells THR. “He has the most pronounced character arc of any of the heroes,” beginning from a place of despair and ending with a feeling that “he is whole and that he is loved.” And Terrio says he and Snyder took the portrayal of the first Black superhero in the DC film universe “very seriously,” adding, “With a white writer and white director, we both thought having the perspective of an actor of color was really important. And Ray is really good with story and character, so he became a partner in creating Victor,” referring to the character’s given name.

When new filming proceeded under Whedon, says Fisher, he came to feel that he had “to explain some of the most basic points of what would be offensive to the Black community.”

After Fisher’s reps were told that Whedon planned to make major revisions to the film, he flew from New Jersey to meet with the filmmaker in L.A. When the two met at a bar, Fisher says, Whedon “was tiptoeing around the fact that everything was changing.” As he left the meeting, Fisher was handed the revised script, which he read twice on the plane back. Gone was Cyborg’s traumatic backstory — his relationship with his mother, whose loving scenes with her son were eliminated, as was the accident that killed her and led to his transformation (the material was later restored in the Snyder Cut version of the film that streamed on HBO Max). “It represents that his parents are two genius-level Black people,” Fisher says. “We don’t see that every day.”

Whedon sent out an email asking for questions, comments or “fulsome praise,” but Fisher says it became clear: “All he was looking for was the fulsome praise.” Trying to strike a jocular tone, Fisher responded that he mourned the loss of the Cyborg material but was moving on. He said he had notes to avoid issues in terms of representation of the character. But in a call with Whedon, Fisher says he had barely started to talk when the filmmaker cut him off. “It feels like I’m taking notes right now, and I don’t like taking notes from anybody — not even Robert Downey Jr.,” he said. Other sources on the project say Whedon was similarly dismissive of Gadot and Momoa when they questioned new lines.

Whedon declined to comment for this piece.

Fisher turned to Johns, who he says had presented himself as a kind of mediator. But Fisher says his ultimate response was, “We can’t make Joss mad.” Publicist Howard Bragman, who represents Johns, denies that but says Johns “recalls suggesting that any creative pitches should happen when Joss Whedon was not preoccupied so he would be most receptive.”

Once Whedon got involved, Fisher says that Johns told him that it was problematic that Cyborg smiled only twice in the movie. Fisher says he later learned from a witness who participated in the investigation that Johns and other top executives, including then-DC Films co-chairman Jon Berg and Warners studio chief Toby Emmerich, had discussions in which they said they could not have “an angry Black man” at the center of the film. Johns’ rep responds that once the chairman of the studio mandated a brighter tone for the film, all further discussions centered on “adding joy and hopefulness to all six superheroes. There are always conversations about avoiding any stereotype of race, gender or sexuality.”

Johns told Fisher he should play the character less like Frankenstein and more like the kindhearted Quasimodo. Fisher says that in order to demonstrate the look he wanted, Johns dipped his shoulder in what struck Fisher as a servile posture. To Fisher, there was a big difference between portraying a character who was born with a disability versus one who had been transformed by trauma. And he felt Cyborg was a kind of modern-day Frankenstein. “I didn’t have any intention of playing him as a jovial, cathedral-cleaning individual,” he says.

Johns’ representative responds: “Geoff gave a note using a fictional character as an example of a sympathetic man who is unhappy and has an inclination to hide from the world, but one whom the audience roots for because he has a courageous heart.”

Fisher told Johns it might be one thing for a non-Black person to write a character for a comic, but it was another for a Black actor to portray that character onscreen. “It was like he was assuming how Black people would respond rather than taking the advice from the only Black person — as far as I know — with any kind of creative impact on the project,” Fisher says.

Fisher says Johns did not yield. “That was the last creative conversation about anything that Geoff Johns and I had. I knew I was on my own,” Fisher says. Johns’ rep denies that he ever dismissed any comments, adding that Fisher knew Johns — whose spokesperson requested that he be identified as Lebanese American — “had evolved traditionally all-white DC properties like Shazam, Justice Society of America and others into diverse groups of heroes” in his extensive work as a comic book author.

Justice League producer Charles Roven, a veteran on DC superhero films dating back to Batman Begins in 2005, says, “I fully empathize with Ray that his character arc … was significantly altered and shortened. I’ve also collaborated with Geoff over many years and found him to be a gracious and humble man. Geoff took it upon himself to put Cyborg in the Justice League comics in the first place and has written more about the character than any other individual except for the creator. He loves the character Cyborg.”

All these tensions were playing out during an extremely stressful time at the studio. AT&T’s $85 billion acquisition of Time Warner, which was announced in October 2016 but didn’t close until June 2018, was still pending. Justice League was a $300 million proposition, and it was troubled. Warners had not been able to match Disney’s consistent success with Marvel movies. Fisher felt that some of the studio executives’ decision-making was driven by fear of losing their jobs.

The tension only escalated when the issue of having Cyborg say “booyah” arose. That phrase had become a signature of the character thanks to the animated Teen Titans shows, but the character had never said it in the comics or in the original script. Fisher says that Johns had approached Snyder about including the line, but the director didn’t want any catchphrases. He managed the situation by putting the word on some signs in his version of the film, as an Easter egg. But Johns’ rep says the entire studio believed the booyah line was “a fun moment of synergy.”

Fisher says he doesn’t see the word in itself as an issue, but he thought it played differently in a live-action film than the animated series. And he thought of Black characters in pop culture with defining phrases: Gary Coleman’s “Whatchoo talkin’ ’bout, Willis?”; Jimmie Walker’s “Dy-no-mite!” As no one else in the film had a catchphrase, he says, “It seemed weird to have the only Black character say that.”

With reshoots underway, Fisher says Whedon raised the issue again: “Geoff tells me Cyborg has a catchphrase,” he told him. Fisher says he expressed his objections and it seemed the matter was dropped — until Berg, the co-chairman of DC Films and a producer on the project, took him to dinner.

“This is one of the most expensive movies Warners has ever made,” Berg said, according to Fisher. “What if the CEO of AT&T has a son or daughter, and that son or daughter wants Cyborg to say ‘booyah’ in the movie and we don’t have a take of that? I could lose my job.” Fisher responded that he knew if he filmed the line, it would end up in the movie. And he expressed skepticism that the film’s fate rested on Cyborg saying “booyah.”

But he shot the take. As he arrived on set, he says, Whedon stretched out his arms and said a line from Hamlet in a mocking tone: “Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you.” Fisher replied, “Joss — don’t. I’m not in the mood.” As he left the set after saying just that one phrase for the cameras, he says, Whedon called out, “Nice work, Ray.”

***

Even before that line was shot, Fisher’s agent had called Warner film studio chief Emmerich to raise concerns about what was happening on set. After Fisher arrived in Los Angeles for additional photography in summer 2017, Johns asked him to come to the DC offices in Burbank. When they met in a conference room, Fisher said he had apologized to Whedon for his part in the conflict, which he had done in the hope of preventing a real rupture with the DC team. Johns responded that having agents call Emmerich was “just not cool.” Fisher recalls: “He said, ‘I consider us to be friends’ — which he knew we were not — ‘and I just don’t want you to make a bad name for yourself in the business.’ ” Fisher took that as a threat. Johns’ rep says he never made a threat but told Fisher that creative differences were not normally taken to the head of a film studio by an actor’s agent.

Fisher was not the only Justice League star who was unhappy. Sources say Whedon clashed with all the stars of the film, including Jeremy Irons. And one Justice League star ended up taking her complaints not only to the head of the film studio but also to the chairman of Warner Bros. A knowledgeable source says Gadot had multiple concerns with the revised version of the film, including “issues about her character being more aggressive than her character in Wonder Woman. She wanted to make the character flow from one movie to the next.”

The biggest clash, sources say, came when Whedon pushed Gadot to record lines she didn’t like, threatened to harm Gadot’s career and disparaged Wonder Woman director Patty Jenkins. While Fisher declines to discuss any of what transpired with Gadot, a witness on the production who later spoke to investigators says that after one clash, “Joss was bragging that he’s had it out with Gal. He told her he’s the writer and she’s going to shut up and say the lines and he can make her look incredibly stupid in this movie.”

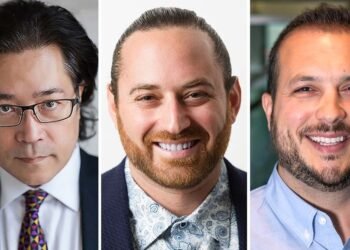

A knowledgeable source says Gadot and Jenkins went to battle, culminating in a meeting with then-Warners chairman Kevin Tsujihara. Asked for comment, Gadot says in a statement: “I had my issues with [Whedon] and Warner Bros. handled it in a timely manner.”

Three months after Justice League hit theaters, Whedon exited Warners’ Batgirl project. “Batgirl is such an exciting project, and Warners/DC such collaborative and supportive partners, that it took me months to realize I really didn’t have a story,” he said at the time.

When Justice League opened in November 2017, the film was panned — it has a 40 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes — and grossed a disappointing $658 million worldwide. Berg exited his job that December; Johns departed the following June.

But Whedon was still part of the WarnerMedia universe: In July 2018, a few months after he left Batgirl, HBO greenlighted his drama The Nevers straight to series. But in November 2020 — just a couple of weeks before WarnerMedia said it had taken “remedial steps” after its investigation into Justice League — Whedon left that project, too. (HBO chief Casey Bloys has said there were no complaints about Whedon’s behavior on that series.) This time Whedon said he was not up to “the physical challenges of making such a huge show during a global pandemic.” Warners issued a clipped “We have parted ways with Joss Whedon.”

***

After Justice League, Fisher went on to play Mahershala Ali’s son in the third season of True Detective, which he calls “a great experience.” But in the coming months, he would hear fresh reports about what had gone on behind the scenes on Justice League, including the “angry Black man” conversation and other allegations involving Johns: Two individuals who worked on Syfy’s Krypton TV series talked to Fisher about events that had taken place on the series.

Multiple sources tell THR that the show’s creators were passionate about doing some nontraditional casting and that Regé-Jean Page, who would go on to become a breakout star of Bridgerton, had auditioned for the role of Superman’s grandfather. But Johns, who was overseeing the project, said Superman could not have a Black grandfather. The creators also wanted to make one superhero character, Adam Strange, gay or bisexual. But sources say Johns vetoed the idea.

“Geoff celebrates and supports LGTBQ characters, including Batwoman, who in 2006 was re-introduced as LGBTQ in a comic-book series co-written by Johns,” says Johns’ rep in an email. Johns also pitched Warners on developing a television show around the first LGBTQ lead DC superhero television series, he adds. As for the role of Superman’s grandfather, the rep says Johns believed fans expected the character to look like a young Henry Cavill.

Several sources who spoke to Fisher around this time were willing to talk to a Warners investigator. Among them was writer Nadria Tucker, who tweeted Feb. 24: “I haven’t spoken to Geoff Johns since the day on Krypton when he tried to tell me what is and is not a Black thing.” Tucker tells THR that Johns objected when a Black female character’s hairstyle was changed in scenes that took place on different days. “I said Black women, we tend to change our hair frequently. It’s not weird, it’s a Black thing,” she says. “And he said, ‘No, it’s not.’ “

Johns’ spokesperson says: “What were standard continuity notes for a scene are being spun in a way that are not only personally offensive to Geoff, but to the people that know who he is, know the work he’s done and know the life he lives, as Geoff has personally seen firsthand the painful effects of racial stereotypes concerning hair and other cultural stereotypes, having been married to a Black woman who he was with for a decade and with his second wife, who is Asian American, as well as his son who is mixed race.”

By late June 2020, Fisher went public with his dissatisfaction at what he viewed as Warners’ inaction. For their part, Warners sources contend that Fisher was being manipulated by Snyder, who hoped to reclaim control of the DC film universe.

Fisher says that “the assertion that a Black man would not have his own agency is just as racist as the conversations [Warners leadership] was having about the Justice League reshoots. I’ve been underestimated at every turn during this process and that is what has led us to this point. Had they taken me as seriously as they should have from the beginning, they would not have made as many foolish mistakes as they did in the process.” Snyder denies any role in influencing Fisher.

Tweeting footage of himself praising Whedon at Comic-Con in 2017, Fisher wrote, “I’d like to take a moment to forcefully retract every bit of this statement.” (His earlier words had been based on studio-supplied talking points, he says.) In a subsequent tweet, he said Whedon’s on-set behavior had been “gross, abusive, unprofessional, and completely unacceptable,” adding, “He was enabled, in many ways, by Geoff Johns and Jon Berg.” He did not elaborate.

Berg told Variety it was “categorically untrue that we enabled any unprofessional behavior.” He added that Fisher was upset about saying “booyah,” “a well-known saying of Cyborg in the animated series.”

As Fisher continued to air grievances on social media and in some interviews, he began to suspect that when he tweeted, the studio would put out an announcement to distract from his message. On July 1 — the day that Fisher tweeted about Whedon’s behavior — Deadline published an exclusive saying Warners was making a live-action Frosty the Snowman movie with Aquaman star Jason Momoa “voicing the iconic snowman.” A few weeks later, Momoa pushed back in an Instagram post. “I just think it’s fucked up that people released a fake Frosty announcement without my permission to try to distract from Ray Fisher speaking up about the shitty way we were treated on Justice League reshoots,” he wrote. “Serious stuff went down. It needs to be investigated and people need to be held accountable.” (Warners says the “Untitled Snowman Comedy” remains in development.)

In early July, Fisher spoke with Walter Hamada, who had taken the reins at DC Films. He says Hamada “called Joss an asshole,” and said, “I’m just looking to get past anything to do with Justice League. Joss isn’t here anymore and I don’t plan on hiring him again.” But according to Fisher, Hamada said he did not believe Johns had done anything wrong. “I don’t know Jon Berg very well. I know Joss was difficult. But Geoff — Ray, he’s really getting dragged through the mud and I’m sure you’re getting your share of hate, too.” Fisher responded, “I’m fine with the hate because I know I’m telling the truth.” He asked for an investigation.

Later that month, the studio’s HR department contacted Fisher; he says he spoke with two executives for about two hours. He adds that he offered specific allegations of abusive behavior toward himself and others, and provided the names of some witnesses willing to be contacted. But he was wary, cognizant that HR departments are often known to show more allegiance to employers than to complaining parties. He became even more suspicious, he says, when witnesses started telling him they had not been contacted. Fisher requested an independent investigator and asked SAG-AFTRA to have a rep with him in the process.

In mid-August, a Warners HR exec told Fisher that an outside investigator had been approved. But his guard went up when the exec said, “We really like him. We’ve worked with him before.” Still, Fisher tweeted that this represented “a MASSIVE step forward!”

But then a Warners veteran told Fisher not to trust the investigation if a particular studio exec was overseeing it because that person had previously helped sweep misconduct under the rug. When he spoke to the investigator, Fisher asked how many times he had worked for the studio. He declined to answer. Fisher asked who was overseeing the inquiry and said he would have an issue if it was the executive named by his contact; he still got no answer. Feeling that the situation felt “pretty dodgy,” Fisher went no further.

On Aug. 26, the investigator provided a name, citing an attorney in the general counsel’s office. When Fisher looked at the WarnerMedia website, he found this individual was the only Black attorney whose headshot was visible.

And in fact, that lawyer had nothing to do with the investigation. (She handled matters for HBO, HBO Max, TBS and TNT.) Fisher wondered if naming her had been a simple mistake or a ploy to lull him “into a sense of security with the idea that she might be on the same team as me simply by way of her being a Black person.”

Feeling ever more distrustful, Fisher continued to tweet, writing on Sept. 4 that Hamada had thrown Whedon and Berg “under the bus” while covering for Johns. “Unfortunately, it’s not until I start talking about people specifically that the needle starts to move,” he says. “If they were going to continue to try to cover things up — I wasn’t going to let that happen.”

Fisher then got a call from Berg, who said he was sorry the actor had an “appalling experience” on Justice League and he hadn’t been able to help. Acknowledging that “a bunch of straight white men” had been running things, he said he hoped the studio would improve on that in the future. Berg said he had spoken to the investigator at length and truthfully. “I let him know that it did mean a lot,” Fisher says. “I’m not beyond forgiveness when it comes to this kind of stuff. It was a very big thing for him to do. No one else in the process has reached out at all.”

The studio, meanwhile, defended itself that day in a statement: “At no time did Mr. Hamada ever ‘throw anyone under the bus,’ as Mr. Fisher has falsely claimed, or render any judgments about the Justice League production, in which Mr. Hamada had no involvement.” The company said Fisher had refused “multiple” attempts by the investigator to contact him. Fisher saw that as a smear.

In early October, top WarnerMedia execs spoke with Fisher and his team, including a rep from SAG-AFTRA. (Fisher’s reps confirm the content of the call.) When Fisher pressed the question of how the investigator had come to provide the name of an in-house attorney who had nothing to do with the inquiry, a WarnerMedia executive on the call responded that the investigator had “just pulled the name off the internet.”

Christy Haubegger — head of communications at WarnerMedia and the company’s top inclusion officer — said on the call with Fisher that the studio’s statement that Fisher had refused to cooperate with the investigation had been based on “third-hand” information. The studio’s communications department had been “responding emotionally” to Fisher’s public allegations against Hamada, she said, adding, “I think they believed what they were saying was true.” Fisher wondered why anyone at the studio, which was ostensibly the subject of the investigation, would comment at all.

Pressed by Fisher, Haubegger declined to say who at the studio had approved the statement, but she said she was “furious” when she read it. “I have made it 100 percent crystal clear to everyone in the entire Warner Bros. communications organization that not a goddamn word can be said about Ray Fisher,” Haubegger said. “If I catch anyone doing that, they’re fired.”

Fisher says he asked for an apology repeatedly in the weeks that followed. WarnerMedia kicked around some language that he felt fell short. Ultimately, Haubegger told Fisher, “I don’t think that if people said something they believed was true that there’s an apology needed.”

After the studio put out the statement accusing him of not cooperating, what Fisher calls “the hit piece,” he asked for another investigator. WarnerMedia agreed to bring in Forrest, who they told him had handled the investigation of ousted CEO Tsujihara. Fisher was initially optimistic but says he again turned wary when Forrest, who is white, led with the fact that she was an Obama appointee. Still, Fisher was somewhat optimistic because he believed Forrest’s previous Tsujihara investigation had exposed alleged misconduct. But she told him that she hadn’t completed that inquiry before Tsujihara left. Instead, he left after THR published an article about his entanglement with aspiring actress Charlotte Kirk.

Initially, Fisher was told Forrest would work alongside the original investigator. He objected and the original investigator withdrew.

In December, Fisher says that he and his SAG-AFTRA rep had a final conversation with Forrest during which she said remedial action had been taken, some of which she said Fisher had probably seen, but she was not explicit. She said further remedial action would be taken but again did not offer specifics. But she told Fisher she did not find evidence of racial animus. (Warner Bros. chairman Ann Sarnoff said in a recent interview that the investigator found “the cuts made in the Joss Whedon version of Justice League were not racially motivated,” but Forrest didn’t say that publicly.) To Fisher, the information Forrest shared was so limited that it seemed the purpose was clear: “She was only authorized by WarnerMedia to attempt to explain away anything to do with race.” Warners maintains it has “complete confidence in the investigation process and her conclusions.”

On the evening of Dec. 11, Warners issued a statement saying the investigation was finished in what Fisher calls “a Friday night news dump.” Witnesses contacted him asking what had happened, but he had no answers. A week later, he pressed Haubegger and other execs for more information. They asked him to provide names of anyone who had told him they hadn’t gotten closure. Fisher said he would not provide witnesses.

In February, he tweeted that Hamada was “the most dangerous kind of enabler” who had shown that he would “blindly cover for his colleagues” and had worked with the studio to “destroy a Black man’s credibility, and publicly delegitimize a very serious investigation, with lies in the press.” (Fisher says he was referring to the September statement that Fisher had refused to cooperate with the investigation, which he feels Hamada must have known about in advance.)

The company responded with a statement from Forrest saying Hamada was “credible and forthcoming” and “did nothing that impeded or interfered” with the company’s investigation. Fisher believes this missed the bigger picture: While he accused Hamada of “undermining” and “tampering” with the investigation in a series of tweets, he says these were specifically in reference to the conversation he had with Hamada in which the executive tried to dissuade Fisher from pursuing his grievances against Johns. Fisher does not, he says, believe that Hamada otherwise actively tried to interfere with the investigation. Sources at the studio, however, point to Fisher’s tweets as evidence of shifting grudges and a lack of credibility.

Before things had gone sour, Fisher was expected to play a supporting role as Cyborg in the planned movie The Flash. In June 2020, Fisher says he had a call with director Andy Muschietti that seemed positive, but the discussion hit a snag when Warners framed a two-week shoot as a “cameo,” offering only a fraction of what Fisher says he should have been paid for reappearing as Cyborg. Warners disputes this. By late September, he was upset by press reports that he was demanding to double his pay.

Ultimately, the studio removed the Cyborg role from the movie. Citing a Dec. 30 tweet, the studio said, “Given his statement that [Mr. Fisher] will not participate in any film associated with Mr. Hamada, our production is now moving on.”

Fisher says he wasn’t surprised. “When I first spoke up, I assumed there was no way these guys would allow me to do my job in peace,” he says. Now working on the ABC anthology series Women of the Movement, Fisher says he knew the struggle could be costly. “I’m not so indebted to Hollywood that I haven’t been willing to put myself out there,” he says.

“I don’t believe some of these people are fit for positions of leadership,” says Fisher, who explains he’s not looking for anyone to be fired. “I don’t want them excommunicated from Hollywood, but I don’t think they should be in charge of the hiring and firing of other people.” Fisher knows he’s not going to win that battle, but he feels a point has been made. “If I can’t get accountability,” he says, “at least I can make people aware of who they’re dealing with.”