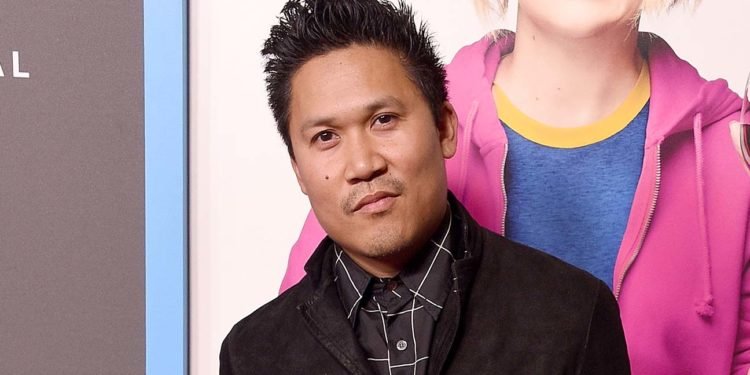

As for Dante Basco, who took on the role (and the tights/jacket ensemble), the look “felt like a goth cowboy.” This is just one of many hilarious revelations fans of Basco and his career will learn when picking up his memoir, From Rufio to Zuko.

Speaking with the actor ahead of the release of his memoir, we quickly connected on both being first-generation kids whose immigrant parents pursued the “American dream” (his family being Filipino, my mother’s family having emigrated from Iran).

That pursuit, and what it meant to Basco and his Filipino family as he grew from a break-boy kid of NorCal to a prominent Asian-American child actor, is a theme that consistently weaves throughout his story and for good reason. Basco, 42, shares that the pages of his book can serve as “a blueprint for the next generation of people of color coming into the city.”

At the start of your memoir, you say you’re “42 years young” and mull over whether you should be writing a book. What made you decide to?

Not a Cult media approached me about doing a book. They’re really cool and do a lot of poetry, so at first I thought I’d be doing a poetry book for them. And they said, “We like your poetry, but we want your story. We want you to tell your story. We want a story of Hollywood from an Asian-American perspective, and you’re the kid that we all grew up with.”

The biggest takeaway from it, by far, is you detailing not just your experiences as a child actor but what it was like to be an Asian-American child actor.

I thought it was interesting and at first, I talked about it in the book, like I’m a little too young to be writing this book. But my impetus while writing, and I kept telling them through edits, I’m really writing this book as somewhat of a blueprint for the next generation of people of color coming into the city.

It reads almost like a diary or a stream of thoughts, filled with anecdotes and advice. Chapter by chapter, it’s very conversational.

Yeah, I had a lot to write. And I’d never written a book before, anyway. I wrote a lot of essays and we put them together.

What was the process in terms of deciding which stories to share between family and your career?

First and foremost, I brought up by my family because we all came here together. They’re all part of my story. I’m all part of their stories. It’s kind of like our story — my perspective of our story. Then, of course, there’s the projects a lot of fans will want to hear about. So I tell some stories about those, some of them from 20-plus years ago, some 10 years ago. Then we just broke it down and I started writing essays.

How long did it take to get everything together?

Like, two years. I didn’t realize until I read the beginning of the book that some events were years ago.

What does your family think of the memoir? Have any of them read it?

Some of them read a little bit. My sister read probably the whole book.

Was there anything particularly challenging to write about or you were worried about sharing?

Anyone who has been in this town long enough has their own True Hollywood story. When you talk about specific thing, there’s abuse that happens sometimes in the industry. You have a kid coming in and dealing with that. … When you’re referencing lessons in our industry that have been really great over my career, I’m also just cautious about how I’m talking about them and not wanting to offend anyone in that way.

Right, but as you said, if you want this to be a guide for those coming into this industry, especially people of color, it’s helpful to be real so negative experiences aren’t repeated or can be avoided. For example, you opened up about an abusive relationship you experienced with an acting coach.

One of the biggest things is my old acting coach. That was a very big part of my upbringing in Los Angeles, as an artist there. I was hoping I was fair in the depiction of my memories — good and bad. I’m very cautious about it because she still has an acting school, she’s still doing her thing. But, also, it wasn’t 100 percent. I’m sure she’ll take offense to stuff.

Something unique throughout the memoir are these inclusions of poetry. You also share how you started Dante’s Poetry Lounge (now the largest weekly open-mic venue in Los Angeles). What does poetry offer you?

I’m a poet, first and foremost as a writer. That’s who I am. That’s what I’m most comfortable writing. So there are some pieces in the book that had not been published and Not A Cult media was, like, “Yeah, let’s throw them in.” It’s just as simple as that, but like when I go out and do talks, I do a lot of keynotes and through a lot of those I read poetry. For me, it’s a smaller way to depict a certain feeling or an event. Just made sense to have a few poems in the book, just a bit of my style in there.

Right, if it’s your memoir, it helps to include that part of yourself. Now, what are some of the biggest reflections you had while looking back at your experiences as a child actor?

I feel like I grew up differently, when you’re a child actor you grow up differently, but it’s not that different than growing up as, like, a child basketball player who goes to the NBA. There are certain kids who become professionals at a very young age. There’s a lot of sacrifice that goes into that. There’s also a lot of pride — but that’s not my style, I come from a different kind of upbringing. I mean, there were ups and downs, and that’s my experience. I didn’t have the regular high school experience. My experiences were on sets.

There’s a line in the book where you mention, “You really start to feel that awe and wonderment when you go to public school and people see you on TV.” And you broke it down as there might be fancy dinners or a big party, but most of the time you’re just doing a job, while friends, family, fans, most often they just see the end result — you’re Rufio! And you express there were a million little things that went into that, that people don’t see.

Right, exactly. I was actually explaining that to my uncle a few nights ago. He was on set, in my hometown. My whole family’s there, coming to watch this shoot. We did a really crazy scene in the Filipino American cultural center [filming for an upcoming project, The Fabulous Filipino Brothers]. And it was super cool and everyone was, like, “I can’t wait for the movie to come out.” And I was telling him the same thing, like, making a movie is like life. It’s not the destination, it’s the journey. The movie is the destination. Audiences see the movie and that’s how they experience it, and that’s great. You may like it. You may not like it. It may turn out bad, but we’re having a great time right now doing it. It is a wild ride to get there. Like, our experience is this whole thing and their experience is the end result.

Now, you touch on all of these roles you’ve had in your career — Prince Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender, General Iroh in The Legend of Korra — how much weight do you feel your role as Rufio in Hook played into helping you with all of these roles, or do you see them as singular achievements.

You’ll never, you’ll never know. I mean, who knows? I mean, for some, you walk in the room and to filmmakers, you’re this legendary figure from their childhood. You’re never going to shake that. Other roles — just because I was in the era of not a lot of Asian-Americans on TV, I was one of the very few Asians that people knew — I walk into other rooms, like years ago, and a guy is, like, “I wrote this role for you.” He’s, like, “That’s the guy who has been on my mind the whole time I wrote this role.” That’s the great thing about having more representation. We need more and it’s happening more.

How well do you feel Asians and Asian-Americans are represented today in film and television in the U.S.?

I think it’s much better than it’s ever been. I mean, the reality is Asians in America are at the highest profile they’ve ever been in the history of this country. That’s great. Doesn’t mean it’s anywhere near what it should be. The great things with films like Crazy Rich Asians have done, in this modern moment, is capture the imagination of everyone in America. It helps spark making more. Even the fact that I’m doing a movie right now, that’s all you can hope for. We’ll see what comes of it all. I’m part of a lot of groups and a lot of discussions about how we can try to keep this going, create really viable self-sustainable, viable systems here that are going to keep Asians in front of the camera, behind the camera, a part of the system. I am excited about it, but it’s going to take a lot of hard work and a lot of continuing work — by Asians and non-Asians creating content.

What do you hope your fans, and newcomers, will gain from reading your memoir?

I feel a little more vulnerable than I have in the past. It’s more vulnerable than it is coming out with a movie because it’s you and your story and your family. Who wants to be judged? Nobody. But here we are, the book’s coming out. What do I want people to get out of it? I really wrote it for the next generation of artists. Like, this is what I was trying to do. This is what we were trying to do. Some bad stuff happened, some really great stuff happened. There’s actually some really great stuff that happened, you know? For those that have known my career and my work, it’s a little bit of a different angle on my journey.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.