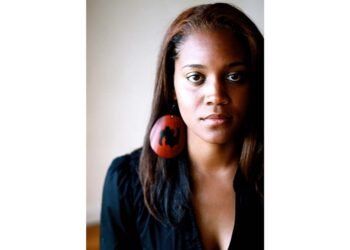

Known for the Why Are People Into That?! podcast, which she created, produced and has hosted since its 2014 debut, Horn is the author of Love Not Given Lightly, a collection of journalism about sex workers in the Bay Area, and has written about sexual politics and queer culture for outlets including Rolling Stone, Vice, Refinery29 and Allure. She has also written written extensively about FOSTA-SESTA, the recently passed law ostensibly put in place to reduce sex trafficking that has, critics say, increased the amount of danger consensual sex workers face in the United States. In other words, Horn is coming to the series with a lot of real world knowledge of the subject matter under her belt.

The Hollywood Reporter talked to Horn about the series ahead of its launch.

SFSX feels very much a book of the moment; did it come from looking at the way things are already going with FOSTA-SESTA and authoritarian crackdowns and going from there? How did the series get started?

I conceived of the series in mid-2017, before I was aware of FOSTA-SESTA, so this has very much been the case of the dystopia catching up with me as I wrote it. Believe me, I take no pleasure in having been too right. As some of my comrades have said, sex workers are the Cassandras in the coal mine of sexual freedom. By the time you register our screams, you’ll know the air is about to be unbreathable for you, too. The line “The Party is here to save you from yourselves!” is very much inspired by attitudes faced by all kinds of people who sexually transgress. Sex workers have to deal people telling us we don’t realize we’re being exploited. Queers have to deal with people telling us the way we love and fuck and make families isn’t valid. Women have to deal with people telling us that not being too slutty is for our own good.

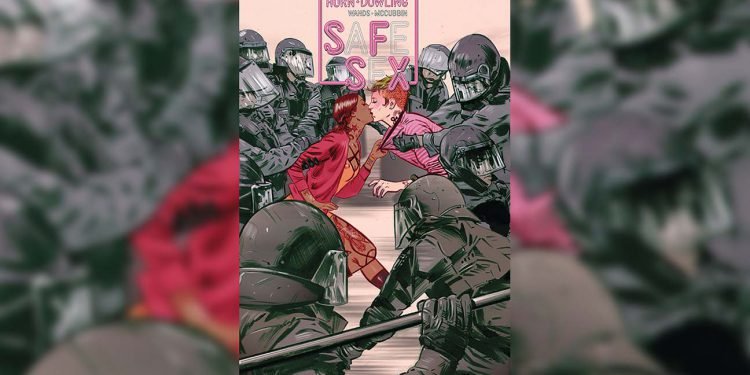

The Party raid on [underground club] the Dirty Mind that opens issue 1 is meant to embody everything from the Stonewall uprising to the Homeland Security shutdown of Rentboy, where I worked in the marketing department. I wanted to begin the story with that trauma: the terror of being under constant threat from police violence, the twin horror of losing friends to incarceration and assimilation. The characters and action of SFSX arose from a very personal and emotional place for me: the tension between safety and conformity.

The way I’ve constructed villainy in this story is meant to demonstrate how homophobia and whorephobia come from the same impulse of powerful people trying to preserve a way of life that they believe will make their concept of family and country safe. And how they marginalize others in order to maintain that sense of safety. I want to ask: why do we think we have to endanger others in order to feel safe? Why do we think we have to screw other people over to survive?

You mentioned the Party, and I want to congratulate you on making it an antagonist that feels at once entirely prescient and also utterly chilling — the idea of storm troopers announcing their appearance by declaring that they’re “here to rescue you from yourselves” is very much the kind of “20 minutes into the future” dystopian horror that makes this book feel worryingly real. The same with the idea of having to file sex with your spouse or else a FitBit will report you to the authorities.

Dystopias should always be satirical, in that they should disrupt our comfortable notions of the fundamentals of power. My collaborator Jen Hickman and I were recently on a Flame Con panel about queer monstrosity, where Hickman referred to dystopias as “institutional horror.” That took my breath away, because it describes the project of SFSX perfectly. This series is definitely science fiction, and a social thriller, and a romantic action adventure, and it’s also a queer horror story. The horror is located in the systems of power; the heroism in the survival strategies of those who must disrupt and dismantle the systems.

What do we learn about our relationship to bureaucracy if, as in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, the absurdity is pitched up just enough to make you realize how Kafkaesque your life already is? What if, as in Bitch Planet, misogyny is institutionalized to enough of a camp extreme that by the time your laughter dies down you realize you’re weeping with recognition? How does a social thriller like Get Out indict me as a complicit white person while also being entertaining as hell?

My goal with SFSX is to make the gatekeepers of sexual normalcy feel the way I felt as a white person watching Get Out. That movie galvanized me to fight white supremacy, because of how effectively it demonstrated that oh yes, it already really feels this violent, this dehumanizing for black people every day in America. You can really see that in issue 1 as Avory tries, unsuccessfully, to navigate an assimilated life: I wanted to portray that feeling of microaggressions as death by a thousand cuts.

The “big bads” of “Protection,” which is the first seven-issue arc of SFSX, are assimilationists who work for the conservative government Party. Their villainy is complicated by the idea that the most marginalized people might also want what conformity offers: safety, resources, comfort, love. When you seek safety, you’re not actively dismantling the system. But the least safe people are the ones who are most motivated to disrupt! So when does self care become an abandonment of principles? When does survival become complacency? I would argue it’s when we abandon our friends and throw more marginalized people under the bus.

“Sex was always my way of telling the world exactly who I was,” from the second issue, feels like the core line in the entire series, speaking not only to who Avory is as a character — and, arguably, who the core audience are for the series, in that they’ll see themselves in there — but also to the price of what’s being stripped away by the Party. To the Party, they’re regulating something that is of little interest or purpose beyond procreation, but they’re… destroying people’s self-identification. It’s not hard to see that as allegory for the country we’re living in right now. How aware are you of the allegorical nature of things, or the direct parallel, even — of how much can and will be read into what you’re writing — when you’re working on it? Is it something you’re counting on from readers?

Supernatural allegory is my jam! My adolescence was shaped by The X-Files and Buffy and Neil Gaiman! But this is not really an allegory. It’s a very literal story. For the kinds of people who are represented by Avory, Casey, Sylvia, and the other characters, the dystopia is already here. Avory isn’t my proxy exactly, but I put a lot of my anxieties into the conflicts she faces. The line you mentioned, that’s definitely a moment where I’m putting my voice in Avory’s mouth. Sexual storytelling is my way of explaining myself to the world. I also try to use it to tell the world about my friends, community, comrades, the people I find beautiful and interesting. I try not to make it all about me!

And yeah, I have a political agenda. It’s to give subjectivity to queers of all kinds, and sex workers and kinky people and sluts, with an understanding of how oppression impacts people differently based on race and class and other factors. The Party says sex doesn’t matter, but of course they know it does! If it didn’t matter then why would they go to all the trouble of regulating and policing it out of existence? Policing sexual freedom means policing all freedom of expression. When an authority says: this is how you’re allowed to express your sexuality, or, this is what is sexual about you and therefore must be made more appropriate, they’re policing how you’re allowed to be in public.

There’s a lot to unpack in the series; outside of the more obvious, attention-grabbing sex angle — there has to be a better way to put that, although it escapes me right now — it’s also a book about Avory coming to terms with who she is… which, to my mind, is somewhere between the crew of the Dirty Mind and the gentrified Bay Area of her husband George and the Party. I don’t want to say it’s a meditation on growing older and moving through social circles, and yet, I can’t get that emotional core out of my head after reading the first two issues. Am I totally wrong? Is there a subtext in there about, for want of a better way to put it, how people can become gentrified and how that impacts interpersonal relationships?

This is absolutely a story about the gentrification of San Francisco. The Dirty Mind, which is colonized by the Party and transformed into [government agency] the Pleasure Center, is physically based on the San Francisco Armory, a place where sexual deviancy was good business for a lot of people, including me, for a decade. Kink dot com was far from a perfect company, but it definitely created a space for queer and kink creative expression and livelihood. There’s a ton of Bay Area cultural specificity in this story, and the omnipresent, Children of Men-style, conservative tech propaganda is there by design.

Avory’s central conflict is one of tension between the subcultures that defined her 20s and the above-the-board life she’s trying to lead now in her 30s. She’s getting older and realizing she’s tired of fighting. Her husband George, the love of her life, can offer her safety. But when she takes advantage of that privilege, she abandons her community. And, as you’ll see, that safety was always an illusion anyway.

Talking about abandoning her community, Avory is met with people across the spectrum of attitudes towards working inside the system in the first two issues, from the Dirty Mind crew to Nick’s guilty pragmatism and George’s more optimistic — and ultimately misguided — sense that everything will be fine as long as you play by the rules. So far, everyone feels (relatively) sympathetic, but there’s also a sense that the Party is going to end up radicalizing each of them by continuing to push its agenda; that’s literally what’s already happening with Avory. Is this an indicator as to how you feel about the issue of activism? That we have to be active participants or else the system will turn on us?

I’m less interested in prescribing how to be an activist than I am invested in the strategies people use to be true to themselves while they’re surviving in a broken system. Avory has been a life-long rebel who is now trying to play by the rules and failing miserably. George believes if you keep your head down and do what you’re told you’ll be left alone and given some privacy. Nick believes in being smartly ambitious, amassing just enough power within the system to be able to afford a secret double life. Jones believes in disruption. Sylvia and Casey believe in keeping underground systems thriving. When their homes are invaded and loved ones are threatened, their values are all put to the test as they have to decide between safety and risk.

I feel like I’m getting too weighty too quickly. I’ll step back to say that one of my favorite things in the first issue is Avory talking about the life skills her sex work experience has given her: Core strength! A “high tolerance for very strong smells”! It’s this wonderfully unexpected moment of lightness at a particularly tense time, and also a subtle pushback to the prudish — and, I’d assume, not-shared-by-anyone-reading-the-book — idea that sexual play is only about sex. Are we going to see more of this going forward?

This book will overflow with sex work subjectivity, and my observations about all the ways that sexual skills, like dancing, bondage, seduction, and glamour, are about physical strength, grace, style, nerve, and versatility. The book has a lot of pleasure for pleasure’s sake, and lots of elements like fisting, group play parties, sex toys, fetishism, and sadomasochism that are totally integrated into the sex lives of a lot of people I know, but almost never seen in fiction. I’m hoping to change that, one vibrator at a time!

I have to ask about artist Mike Dowling. He brings such wonderful acting to the early issues of the series, and a great sense of understated reality to the title. What is it like working with him? Has seeing his work changed the way you’re working on future issues?

Mike is such a solid artist. His painting background makes him very technically proficient, and I see new things every time I look at his panels. I love his realism and grit. He really laid the foundation for this series.

Due to scheduling conflicts, his last issue will be No. 4, but I’m super excited to have a pop-in issue 3 by Alejandra Gutiérrez, whose pop eroticism and humor is going to blow everyone away. After that, I’m bringing on the aforementioned Jen Hickman as the primary interior artist! Hickman and I worked together on a story for the anthology Theater of Terror and I’m just so glad to be collaborating with someone so invested in queer cultural storytelling and aesthetics! I also have to shout out our cover artist, Tula Lotay, who makes sophisticated images that reach out and grab me by the collar every time I lay eyes on them!

Perhaps an odd question, but what kind of pushback are you expecting from the release of this book? There’s no denying that there’s a vocal minority of conservative comic fans who’ll complain about anything that’s not written for the male gaze, and SFSX is… very much not their kind of thing. But it’s also a political book — socially as well as party politics — which is also likely to draw attention. You’ve been writing about sex work and sexual identity for long enough to be able to deal with, or, at least, be aware of, the kinds of pushback such topics get, but do you consider the potential blowback from approaching these topics in comics to be anything different?

I don’t really care about those people and what they think. I’m much more focused on giving sex workers and queers something we don’t get enough of in fiction: subjectivity, specificity, adventure, and joy.

I’ll end on a more upbeat flip side to the above: SFSX may be a recognizable rebellion/uprising narrative, but it’s in a framework and dealing with topics that definitely aren’t the comic book norm. It’s going to be the comic a lot of people have been waiting for, I think. Are you excited for people to get to see what you’re up to? Do you think it’s going to help comic readers expand their horizons — or, even, bring new people already familiar with your work to comics?

I am a lifelong fan of everything from ’60s counterculture trash like Raw Magazine, to indie weirdos like Dan Clowes, to ’90s adventure series like Sandman and The Invisibles, to contemporary sci fi like Saga and The Wicked + The Divine. I feel like SFSX is everything a comic book should be: erotic, suspenseful, melodramatic, and gross, with diverse high quality art, snappy funny dialog, and babes you can care about. I hope it’s also a chance for fans of my journalism and podcasting and other work to be introduced to comics, and for comics fans to be introduced to very real worlds they always thought were just fantasies.

***

SFSX No. 1 will be released digitally and in comic stores Sept. 25.