One of Chicory: A Colorful Tale’s most pivotal scenes begins with a dark room. Eyes track and trace across the otherwise black screen, the crude drawings of neon eyes lighting up the space. My character, a dog I named Pancake, must face the inverted version of itself in a split-screen fight.

In taking on the weight of a magical paintbrush’s legacy, Pancake must contend with a devastating corruption in self-doubt and personal worth, which comes to a head in this particular moment.

It’s the literal interpretation of a sort of internal battle that’s familiar to so many people, the light taking on the dark and spun into a luminous, centerpiece battle that’s reimagined what this sort of fight could look like. Chicory’s biggest bad is not just imposter syndrome, but something bigger: a societal system that doesn’t actually support the animals of its world.

Pancake is not particularly special. The star of Chicory: A Colorful Tale inherits the game’s magical paintbrush and its powers by happenstance. But that power, to bring color back to a devastated black-and-white world, is profound.

This is how Chicory begins, with Pancake picking up that brush and starting to paint. They’re taking over for the brush’s previous “wielder,” Chicory, who’s seemingly abandoned their post, weighed down by the pressure the title of wielder brings. Chicory is about art and legacy, about worth and worthlessness, about believing in yourself, or not. But it’s also about tearing down systems that no longer serve you and your community, about imagining a new world that’s less about competition and hierarchy, and more about equity and mutual aid.

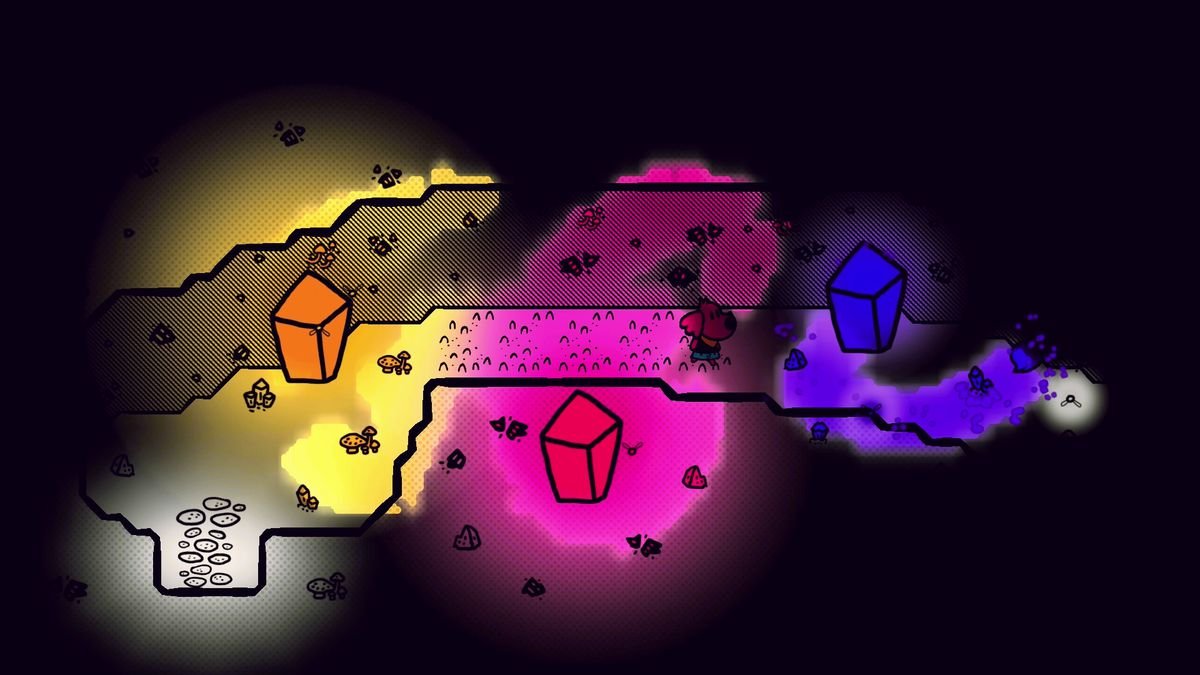

This story is told in chapters as Pancake brings color back to the otherwise-colorless world, a place that’s tangled with puzzles and mazes. The coloring mechanic is essential in getting through the world. Objects change and grow when they’re filled in. A tree that’s blocking a path can be retracted by erasing its color, creating a clearing to walk through. Color it in again and it’ll return, stable enough to use as a bridge between platforms.

Throughout the chapters, Pancake’s bond with the brush will grow, and with it, the things they can do with it change. From simple things, like the ability to jump, to being able to “swim” through paint like one of Splatoon’s Inklings, new, layered mechanics let Pancake access more of the world. With each new upgrade, the bond grows stronger … as does the burden of the brush.

Everything the game conveys to me is gentle and encouraging. The other animals of the world (all of which also have food names) support and believe in Pancake as the new brush wielder. I am constantly reminded of their support, whether that’s Pancake’s sister telling them it’s OK to say no to extra side quests if they’re feeling overwhelmed. Pancake’s parents are always a phone call away to offer useful tips to lost players.

Even in Chicory’s boss battles, which are frantic and bright, I knew it was OK to fail. I could always take another chance without consequence or lost progress. In Chicory, the battle simply pauses, and I’m asked whether I’d like to increase my hit points. Yes or no, the battles simply begin again, right from where it left off. This is not to say that Chicory is an easy game. It’s not. Puzzles require thought and creativity, while the boss battles need a special sort of coordination. These are showpiece battles wherein the big bad takes different forms, each one surprising and inventive in their own right, reflecting the terrors of legacy and doubt.

Image: Greg Lobanov, Alexis Dean-Jones, Madeline Berger, Em Halberstadt, Lena Raine/Finji

Even while I take my time, there’s an encroaching negativity tied to the corruption overtaking the world — a literal and metaphorical darkness that’s increasingly affecting Chicory, Pancake, and others nearby. The darkness manifests in the characters’ thoughts: “What makes someone worthy of wielding the paintbrush?” “Are we worthless when we can’t?” Former wielder Chicory was destroyed by the pressure of the brush’s power, while Pancake grapples with not being worthy to be “chosen” by the brush. The juxtaposition of Chicory’s lightness and darkness creates a necessary balance. Without it, the game might have felt overly sweet or unnecessarily grim. Instead, Chicory’s earnestness in the highs and lows finds the perfect tone.

It reminded me, in some ways, of a game I played right before Chicory, Studio Fizbin’s Minute of Islands. Aesthetically and gameplay-wise, the games have little in common. The similarity lies in the themes: the darkness of self-doubt and depression. Another comparison I’ve seen for Chicory is the Legend of Zelda franchise, and there’s no doubt the team of developers drew inspiration from that game’s top-down puzzles. But, like Minute of Islands, Chicory subverts the trope of the hero, the systems and hierarchies that name a chosen one, the only one worthy of wielding some powerful tool.

Instead, Chicory asks, “What if there’s a better way?” A person’s worth is inherent, and it’s not chosen for us. If we tear down those systems and rebuild something new, we can shift legacies and choose them for ourselves — it’s no longer a gift bestowed upon us by some unfair, undated structure. With a little practice, maybe anyone can wield a paintbrush.

Chicory: A Colorful Tale was released June 10 on Mac, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, and Windows PC. The game was reviewed using a Windows PC download code provided by publisher Finji. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.