Director Rodney Ascher has an interesting approach to the documentary form. His 2012 film Room 237 explores fan theories and coded messages within Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, with its subjects asserting that the film is Kubrick’s confession that he faked the Moon Landing. But the film isn’t really about these theories — it just uses them as a backdrop to explore the people Ascher is interviewing. It’s a film about obsession and searching for hidden meanings, which makes it a fitting prelude to Ascher’s latest, the simulation-theory-centric A Glitch in the Matrix.

The philosophy that the world we see is somehow false goes back at least as far as ancient China, India, and Greece. But the Wachowskis’ 1999 action classic The Matrix mainstreamed the modern version of simulation theory, which claims we’re living in an illusory reality. “Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real?” the film’s heroic leader Morpheus asks newbie protagonist Neo. “What if you were unable to wake from that dream? How would you know the difference between the dream world and the real world?”

Human civilizations have always contextualized consciousness through the lens of the technology available to them. The era of irrigation ushered in the theory of humors, the idea that our emotions are regulated by the flow of liquids in our body. Medical advancement proved this untrue. Electricity shepherded in a different understanding: scientists started likening the nervous system to a grid carrying electric impulses from one point to the next. With the advent of computers, we began to define the brain as an advanced computing mechanism. Now, we live in the age of video games, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence, and simulation theory seems like a similarly natural outgrowth.

Image: Magnolia Pictures

The theory was famously espoused by the mid-20th-century science fiction novels of Philip K. Dick, which formed the basis for films like Blade Runner and Total Recall. Dick himself claimed to have memories of an “alternate present,” and footage of him making these claims appears throughout A Glitch in the Matrix, taking up a not-insignificant chunk of the runtime.

In reality, Dick’s claims were likely tongue-in-cheek, but the film presents them sans commentary or judgement, because neither Dick nor the veracity of his claims are the documentary’s focus. The film presents these ideas as seriously as they’re taken by its subjects, a group of young and middle-aged men who provide Ascher with remote interviews about their thoughts and experiences, and discuss how they first came to believe they were living in a digital world. To enhance the audience’s understanding of their perspective (and perhaps to hide their identities), the film presents these subjects in the form of digital avatars occupying their respective living spaces, as if they’d turned on futuristic Snapchat or FaceTime filters.

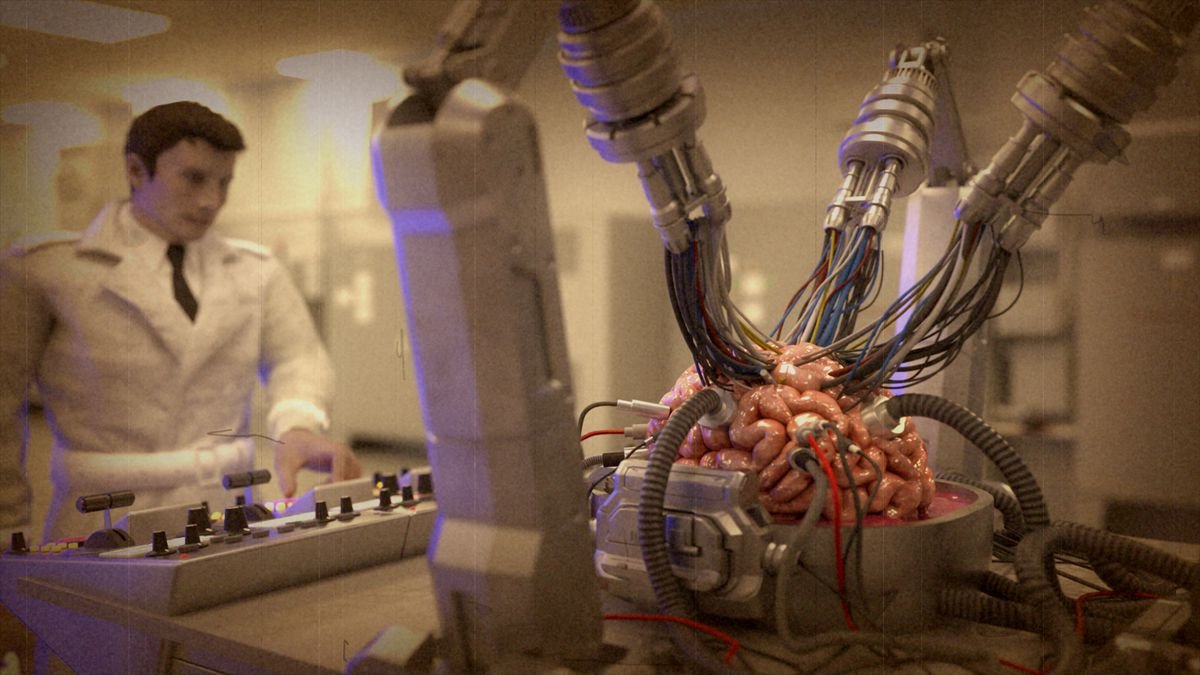

One of these avatars looks like a kaleidoscopic Lion-O from ThunderCats. Another resembles a neon Anubis by way of Transformers. Two others feel like steampunk and post-apocalyptic variations on one of the film’s major themes: they look like brains hovering in fancy jars. Their voices are largely unaltered, and they speak matter-of-factly, often with a tinge of self-deprecation, as their avatars move to replicate their gestures and expressions. The edit even captures mundane details that would feel extraneous in any other documentary, where the focus would be on what these talking heads were discussing, rather than the talking heads themselves. They interact with people off-screen, around their respective homes — it brings to mind an unseen subject of Room 237 comforting his crying infant over footage of The Shining — and one subject’s vape pens even gets its own digital equivalent.

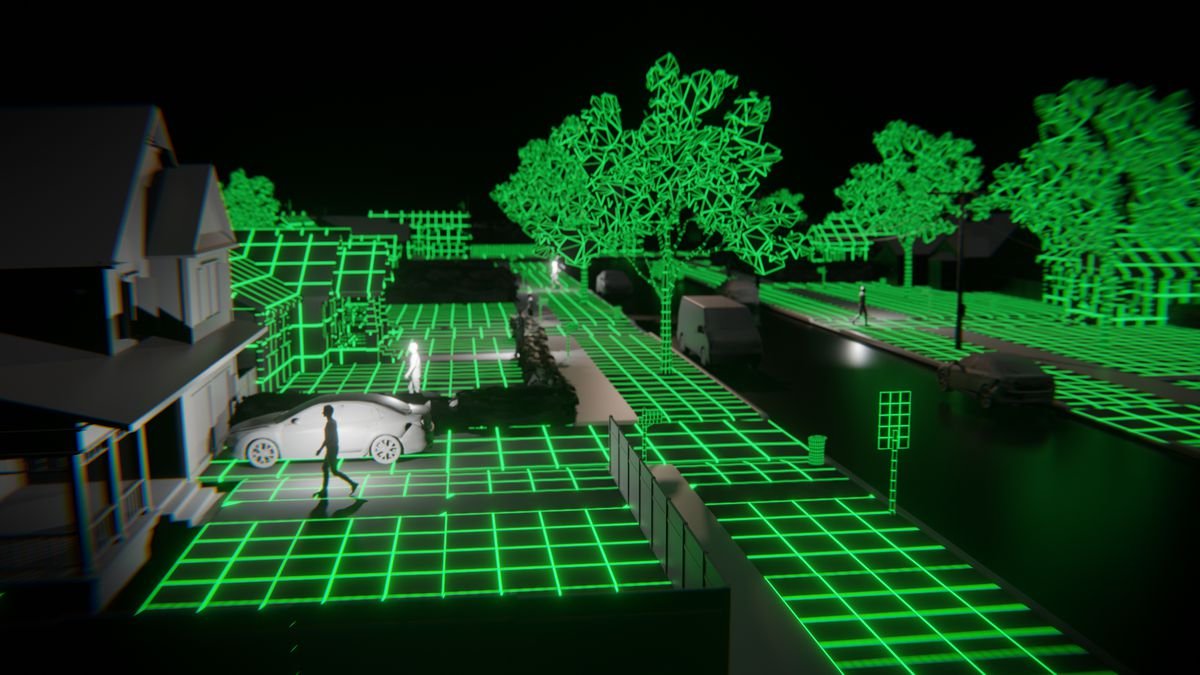

The story Ascher tells isn’t just what these people believe, but why they came to believe it. After a detailed exploration of the theory and its historical roots — over footage of Minecraft and other video games, to introduce us to the concept of programmed non-player characters, or NPCs — the film delves into digital re-creations of the subjects’ experiences. Some re-enactments resemble moments of mental dissociation, which the film visualizes as luminous deconstructions of the interviewees’ digital selves. Others simply unfold as instances of paranoia and strange, uncanny memories re-told from the avatars’ perspectives. The more context Ascher provides about the theory, through academic and journalistic sources, the more he allows each subject to reveal about themselves through first-person accounts.

The avatars are like friendly, offbeat cartoon characters. After a while, they begin to seem vulnerable, especially when the subjects open up to Ascher, and they come off as desperate to understand the world around them. Like Neo before he’s “awoken,” they’re grasping at some nagging, unspoken feeling they can’t put into words — or couldn’t, until they came across various science fiction stories that did.

While the film never attempts to justify these perspectives, it dramatizes them with conviction. The retelling of the subjects’ experiences is particularly compelling, and it offers a precise window into the kind of doubts and disconnects underlying their beliefs — viewers are unlikely to agree with them, but the odds of understanding them are high.

Image: Magnolia Pictures

One subject describes his mental dissociation while attending church, a space the film visualises as if it were a Star Trek holodeck — the famous artifice-generating device, which reflects the subject’s feelings about his physical self. Other subjects mention their isolation from friends and family, and seem convinced of some invisible hand programming or guiding the physical world. The theory is pseudo-religious in nature, existing at the nexus of faith and simulation explored by Dick in his story “Adjustment Team,” which went on to become the film The Adjustment Bureau. It seeks to answer some of the same questions asked by religion: the “how” and “why” of human existence, and what comes after death. Drawing these comparisons helps Ascher make his interviewees feel more human as they latch on to simulation theory in order to quell their existential anxieties.

As editors, Ascher and Rachel Tejada ensure the film moves at a mile-a-minutes pace, jumping as quickly from topic to topic as the subjects themselves. After a while, the film begins to feel like a sensory experience, as Jonathan Snipes’ ethereal musical soundscape makes the re-enactments feel hauntingly immersive. The filmmaking becomes an emotional Trojan horse, smuggling viewers into these subjects’ lives and the way they process information. Then Ascher seamlessly introduces a new subject whose story speaks to the worst-case-scenario of these beliefs.

There’s a built-in dark side to any conspiracy theory. Where there are strings, there’s the question of who’s pulling them, and how far you’re willing to push to break free. After creating a sense of comfort through his more personable subjects, Ascher arrives at a well-earned tonal shift which weaponizes that comfort. What’s the harm in disbelieving reality if no one gets hurt? Well, eventually, someone will. This additional subject doesn’t appear onscreen, but Ascher offers up his haunting, disembodied voice. It sounds as though he’s been cut off from his physical self as he confesses how his sense of isolation, and his unease with his own existence, drove him to violent extremes.

The narrative subversion involved in this sudden twist is possible because of the digital gimmicks Ascher employs to make viewers empathize with his subjects. The more he reveals about their humanity, the more compelling they become, even in non-human forms. He turns the film into an intimate, subjective look at why people might be driven to such theories in the first place. While simulation theory doesn’t have the overt political dimensions of something like QAnon — one of several sprawling conspiracies that gave rise to the recent storming of the U.S. Capitol — the film places the audience in the uncomfortable position of having to relate to the vulnerabilities that send people down conspiratorial paths.

Viewers might even recognize some of those vulnerabilities within themselves. That’s an unsettling notion born from the film’s dramatic deftness. But it seems necessary to swallow this pill if we’re to avoid tumbling down similar rabbit holes. We may not be as different from these subjects, or as immune to their way of thinking, as we might like to believe.

A Glitch In the Matrix is now in theaters and available for digital rental at Amazon and Vudu. Before visiting a movie theater, Polygon recommends checking our guide to local safety conditions and theater protocols.