Video game quests come in all shapes and sizes.

There are big, splashy main-story quests. There are quests that reveal the dark backstory of one of your compatriots. There are the obnoxious follow-that-stranger-without-being-seen quests. And then, at the very bottom of the unspoken quest hierarchy, there are … fetch quests.

After years of wondering what Death Stranding actually is, I can finally report that it’s a game composed entirely of fetch quests. Forty-plus hours of that may sound like torture, but shockingly, it’s actually pretty damn fun once it gets out of its own way.

Bringing America together again

Before you start delivering boxes to and fro, you should know that Death Stranding’s story is weird. I’ll spare you the intricate lexicon that Hideo Kojima created to describe every bizarre paranormal phenomenon, but here’s the quickie version: Most of America is gone because ghosts showed up and killed people. When those people died, their bodies blew up. And people caught in those blasts also blew up. The initial event was called the Death Stranding, and it wiped out a very large chunk of America’s population. All that remains are small, walled city-states, completely cut off from one another.

Now there’s an immediate need for “porters” — people assigned to deliver supplies to the different cities, risking their hides in the dangerous wastelands of America — in this new, splintered country. That’s where Sam Bridges (Norman Reedus) comes in. He has developed a reputation as a top-notch porter, and is enlisted by the president — who also happens to be his mom (!) — to travel the wastes and bring the isolated cities back into the fold by connecting them to a fancy data network. “If we don’t all come together again, humanity will not survive,” the president says.

This all sounds pretty grandiose, but the actual process of reconnecting the cities is far simpler: Sam walks there, asks if they’re up for it, and jacks them in during a cutscene. Some of the inhabitants take some convincing, asking Sam for a favor or two before he can plug in the Ethernet cable. Then, once they’re on the grid, Sam continues making his way west.

The actual walking in Death Stranding is incredibly complex: Each small rock or ledge is capable of tripping Sam, sending his packages flying. I find myself constantly scanning the environment, surveying the landscape to find the smoothest possible route through a perilous rocky outcropping. There’s no automatic parkour or physics-defying cliff climbing here. Every step I take needs to be intentional, or I might end up taking a serious tumble. When I overload my pack I have to use the left and right triggers to balance my weight, or else I risk falling over, damaging my goods. It’s equally engaging and frustrating as I topple over after twisting my ankle, forcing myself to restack all my belongings. Death Stranding is a walking simulator in the truest sense.

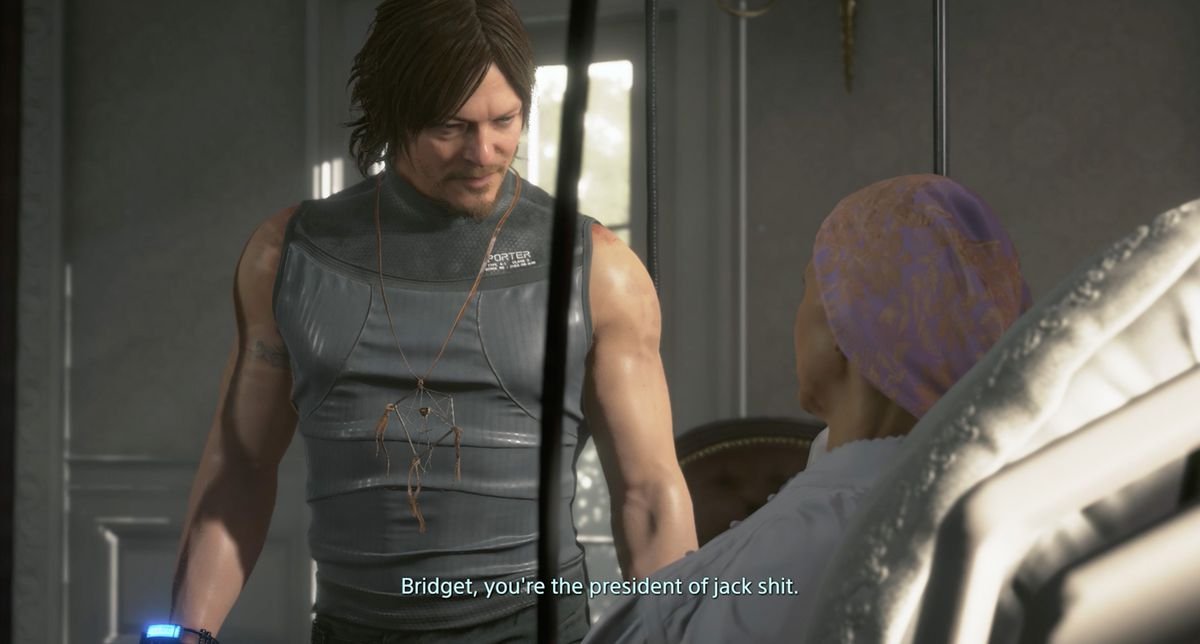

Kojima and his team devote Death Stranding’s first 10 hours to breaking up the walking gameplay with melodramatic cutscenes that seek to explain the game’s world. These cutscenes are outrageously overwritten and long, frequently stating (and then repeating) the same talking points, dragging the pace of the introduction to an absolute crawl. This is, after all, a Kojima game, and he’s nothing if not verbose. The stilted, over-the-top writing frequently gets in the way of some solid performances, notably from Reedus and from Lindsay Wagner as Sam’s mother, the president.

It’s a true feat to be able to deliver some of the game’s dialogue in a convincing way (e.g., “Bridget, you’re the president of jack shit”). While some of the actors can pull this off, others, like Léa Seydoux (who plays a character called Fragile), have a tough time selling the emotion of the stiff writing. There’s also the weird sense that Kojima tried to jam many of his famous friends in as cameos, with mixed results. Director Guillermo del Toro wisely provided just his likeness for one of the main characters, Deadman, leaving the voice acting to Jesse Corti, who does a solid job. But then Conan O’Brien shows up in a side mission, and suddenly the illusion of this world is dashed.

The story’s best moments depart from Kojima’s technobabble — “a cryptobiote a day keeps the timefall away,” says Fragile at one point — in favor of telling personal stories about the survivors of this twisted world and what motivates them to keep going. A boyfriend and girlfriend longing to be together, yet separated by an impassable desert of death. A pair of sisters who haven’t spoken in years but still share some kind of connection. These smaller stories are the ones that click in Death Stranding.

The larger, grander tale — about the apocalyptic “Death Stranding” itself, the mystery of what caused it, and the challenges of fixing it — ends up feeling wooden in comparison.

Delivery man, reporting for duty

It takes about 10 hours for the throat-clearing to wrap up and for Death Stranding’s structure and mechanics to fully reveal themselves. And those 10 hours are some of the weakest in the game, thanks to the endless cutscenes and a series of bummer quests that have me lugging packages (and even a corpse!) up steep hills in the rain. I’m never given a great reason for these initial chores; I do them because I’m told I must. It is the epitome of a slog, and it’s easy to imagine that many players won’t ever make it past this stretch of the game.

But even if you do, here’s the thing: The entire game is about lugging packages. That’s what you’ll be doing whenever you’re in control of Sam: bringing a box or boxes from one part of the map to another. Saying it out loud, it sounds like absolute misery.

Something clicked for me after those first 10 hours, though. The basic loop of many open-world games involves starting out as a puny nobody and, over dozens of hours of exploring a wide expanse, gaining wondrous abilities to become a walking god. But that never really happens in Death Stranding. Sam essentially has the same abilities at the end of the story as he did in the beginning. A few handy gadgets and a little extra carrying capacity, maybe. But generally speaking, he’s the same ordinary guy with a stack of boxes.

Combat sequences emphasize his limited skill set, as he’s better off avoiding conflict rather than dealing with it head-on. Occasional missions that require Sam to mix it up with people as he goes about his delivery route feel almost like an afterthought compared to his normal day-to-day travails.

Something does evolve over the course of Death Stranding, but it’s not Sam; it’s the world around him. I put a ladder on the ground, creating a makeshift bridge to cross a river that may ruin some of my cargo. That ladder then has a chance to show up in other players’ games, making their own trip across the river easier. It works the same in reverse, as I suddenly start seeing helpful ropes, ladders, and footpaths popping up in this ruined America, placed there by other folks playing the game.

Kojima Productions/Sony Interactive Entertainment via Polygon

These player-made structures don’t show up until I’ve connected a specific region to the network. The areas are barren and wild as I begin to explore them, but over time, they slowly become civilized, with some zones dramatically transformed in the process.

There are plenty of hazards in the world of Death Stranding, and the aforementioned ghosts who kicked the whole mess off are some of the worst. Called BTs (for “beached things” … because reasons), the ghosts make it incredibly dangerous to cross open plains, requiring stealth and constant awareness.

Sam’s jar-enclosed baby (they’re called BBs; his is BB-28) is the star during these sequences. Humans can’t spot the ghosts with the naked eye, but BBs can. They don’t offer you radar on a minimap, though. All you get is a constant flashing and pointing of Sam’s back-mounted mechanical arm, which the BB controls to indicate the location of the nearest ghost. There are ways to aggressively handle the BTs later in the game, but in the early hours you’re just supposed to avoid them, as silently as possible. This proves especially difficult when you’re lugging a steamer trunk filled with — let me check my notes — ah yes, sperm at one point. At least that’s better than the corpse?

Kojima Productions/Sony Interactive Entertainment via Polygon

There’s one acre of land I keep having to cross for deliveries that’s absolutely swarming with BTs. Whenever I get snagged by accident, sticky tar appears around my feet. I once spent too much time in the muck, and was suddenly dragged 50 feet by a massive, tar-covered sea beast (again, because reasons) that seemed none too concerned about the much-needed sperm I was carrying.

The world around me transformed as tar sprang up everywhere, leaving just a few safe places to jump to. I had no idea what was happening or why, but suddenly I had to escape this thing, while trying to gather up my lost belongings amid the chaos. It was an outrageous visual spectacle, but not one I wanted to keep seeing, as it definitely made the task at hand considerably harder.

But I slowly make my way through, time after time, becoming a true ghost-dodging master. While I became adept at these sequences, I wouldn’t call them super fun to play. They feel more like a game of Marco Polo, but instead of asshole cousins around a pool, it’s tar-summoning monster whales.

So I decide to make an investment. Instead of lugging another package, I load up Sam’s backpack with a ton of materials and hike out with a plan: I’m gonna build a goddamn highway right over these ghosts. This requires thousands of materials (earned from doing quests for various cities) and can be a huge resource sink, but it’s absolutely worth it. Once constructed, the road stretches right over the land where the BTs hang, neutralizing them entirely. An area that previously took me 10 minutes of careful stealth to cross now takes seconds.

Kojima Productions/Sony Interactive Entertainment

Not only does my highway save me a ton of time, it also starts showing up in my friends’ games. They message me photos of them driving on my highway, thanking me for the investment. It’s enormously satisfying, even if it does ruin the natural splendor of this once-wild Scandinavian-esque landscape. The vistas in Death Stranding are astonishing, some of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen in a game, and it’s a shame to see them slowly cluttered with ugly ladders and roads. But hey, that’s progress.

There are more opportunities to build on, and civilize, this land as the game continues. By the end, the world is unrecognizable from the untouched wilderness you first set out to explore and connect. It’s now a delivery man’s paradise, with every nook and cranny designed to make each shipment slightly easier. You are, quite literally, optimizing the world. Jeff Bezos would be thrilled.

Interestingly, for a game that has a whole lot to say about politics, familial strife, and the nature of humanity, it never really comments on the potential downsides to this loss of natural beauty. Apparently it’s all great! I can’t really argue that, because thanks to progress, I now get to speed over those goddamn tar demons on my awesome highway.

One could say that the satisfaction I felt upon building the road would have been dulled if I had reached that point sooner (i.e., without the game’s drawn-out, sloggy intro). Without the suffering, I might not have appreciated the end of that suffering. In short, is Death Stranding just giving me a bad case of Stockholm syndrome? Does it matter?

Kojima Productions/Sony Interactive Entertainment via Polygon

Kojima giveth, Kojima taketh away

Having been smitten by the core world-building gameplay of Death Stranding, I am stunned to realize that many of the game’s strongest, most appealing gameplay ideas (specifically the world-building and cooperation) are tossed aside in the final acts, in favor of a much more linear, scripted, cutscene-ridden experience. The freedom and sense of ownership I enjoyed while creating this world are dashed in favor of explaining and wrapping up a story that never had much going for it to begin with.

The final 10 hours of Death Stranding are a slog, just like the first 10 hours, as my leash is tugged from emotional monologue to ridiculous boss fight to emotional monologue. While a few of these narrative threads make sense and land with some gravitas, others sound like the ramblings of someone on speed who thinks they’ve figured out how the universe works.

Death Stranding feels like two games in one, designed for seemingly opposite audiences. One is a wholly unique open-world adventure with asynchronous cooperative multiplayer that allows me to feel like I’m part of a community, building a world from scratch. And the other is a long, confusing, deeply strange movie. The former is pulling most of the weight, but they share equal screen time. And, like a steamer trunk full of sperm, it’s impossible to separate the good from the bad. It’s all in the same box.

Death Stranding will be released Nov. 8 on PlayStation 4 and in summer 2020 on Windows PC. The game was reviewed using a final “retail” PS4 download code provided by Sony Interactive Entertainment. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.

Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. For more information, see our ethics policy.