In the opening minutes of Edgar Wright’s documentary The Sparks Brothers, a who’s-who of musicians and entertainers talk about why they love Sparks, a long-running art-rock band led by brothers Ron and Russell Mael. The likes of Beck, Flea, Jack Antonoff, “Weird Al” Yankovic, Mike Myers, Fred Armisen, Patton Oswalt, and Neil Gaiman all pledge allegiance to the Maels, who for more than 50 years now have been recording and performing snappy and conceptually complex songs, while also remaining obscure enough to retain an air of mystery. Toward the end of the intro, Jason Schwartzman nods to the duo’s mystique by saying he isn’t even sure he wants to watch Wright’s movie. He’s worried that knowing too much about Sparks will spoil their magic.

Sparks belong to a subset of musical acts whose fans either share wide and voracious musical tastes, or tend to think most contemporary pop music sucks. Sparks-lovers have a lot in common with devotees of Frank Zappa, They Might Be Giants, Ween, and Weird Al. Some enjoy the finer nuances of the band’s sound; others appreciate the Maels’ sense of humor, which often pokes fun at musical conventions.

The Sparks Brothers should appeal to those different kinds of Sparks fans — as well as to folks like Schwartzman, who’d rather not know how they pulled off their trick. Wright takes an exhaustive approach to the band’s career, going album by album, talking to collaborators and supporters as well as to the Maels. Throughout, Russell and Ron remain somewhat aloof, perhaps by design. They’re more open about their past and their intentions here than they’ve ever been in interviews, but they aren’t about to give away all their secrets.

The film’s rarest material comes early, as the Maels look back at their middle-class boyhood in southern California, as the children of a Hollywood-adjacent graphic designer who died when the brothers were still fairly young. That experience strengthened their bond, which they carried with them as they studied film at UCLA, taking enduring inspiration from the artier ends of the French New Wave. They became regulars at the Sunset Strip rock clubs in the 1960s, in the era of the Byrds and Love. When the Maels started making their own music, they drew attention right away for songs combining retro rock and eccentric experiments, with Russell’s boyishly high but operatically strong voice applied to songs about girls, quirky characters, and pop culture itself.

Wright has access to photos and video from those years that haven’t been widely seen, given that Sparks back then weren’t exactly superstars. But the doc really picks up steam once it reaches 1973, when the brothers moved to England, put together a new backing band, and recorded their landmark third album, Kimono My House. The record featured the smash UK hit “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us,” a pounding anthem with elements of prog-rock and glam, two genres dominating Europe at the time. For about three years — until their sales started to dip — Sparks were ubiquitous on British television. So Wright has a lot of great old footage to pull from.

In 1976, the Maels returned to Los Angeles, and for roughly the next decade, their career followed a pattern. Occasionally, one of their songs (like the jaunty New Wave ditties “Cool Places” and “I Predict”) or LPs (like the hugely influential Giorgio Moroder-produced synth-pop album No. 1 in Heaven) would bubble up somewhere close to the mainstream. Sparks were never part of any particular music “scene,” per se, but the band’s sound was often at least adjacent to hip trends, and the brothers had fans throughout the industry. (At one point in the doc, Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers says that when he first moved to L.A. he assumed Sparks was one of the biggest bands in the business, since they always seemed to be headlining every A-list venue in the city.)

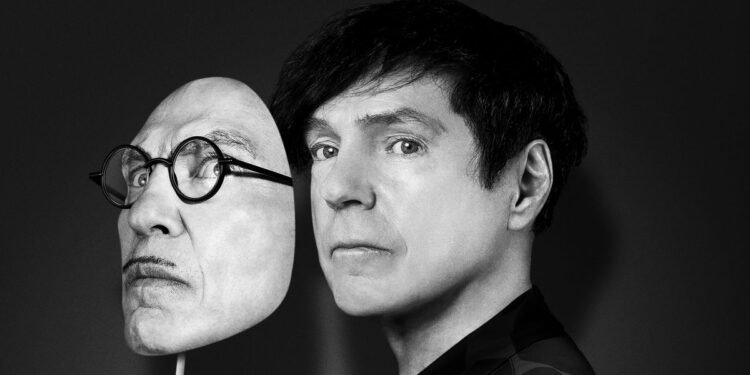

The Maels took advantage of MTV’s arrival to cement their public image: Russell as a shaggy-haired pop-idol type, earnest and performatively vacant, and Ron as a gangly weirdo with a Hitler mustache and cocked eyebrow. Throughout the 1980s, they continued to appear on television a surprising amount for a marginally popular cult act. (Being L.A.-based probably helped. Certainly that’s the best explanation for why they were frequent guests on Dick Clark’s teenybopper dance show American Bandstand.) Yet few interviewers at the time could coax the brothers into revealing much about themselves.

Wright doesn’t have much better luck. The Maels say next to nothing about their personal lives, aside from one brief mention of Russell dating his “Cool Places” duet partner Jane Wiedlin. They say very little about their relationships with their many bandmates over the years, about their impressions of the hundreds of acts they’ve shared bills with since the 1970s, or about their musical philosophies and techniques. We do discover that the brothers meet up almost every day to work together; but we only get the barest glimpses of that process.

In other words, while Sparks fans certainly shouldn’t miss The Sparks Brothers, they likely won’t learn much they don’t already know. Wright’s focus — perhaps necessarily — is more on explaining to newcomers why this oddball act is so beloved. Along with the celebrity testimonials and old TV clips, Wright employs multiple forms of animation, effectively turning the Mael brothers into the abstracted heroes of their own offbeat adventure story. The film portrays Sparks the way many people who love the band see them.

The Sparks Brothers is unusually long for a music documentary, and it’d be a stretch to say that its 140-minute runtime zips right by. Wright avoids one of the common flaws of rock docs, which often peak with their artists’ biggest hits, then compress the remaining decades of their careers into the final 15 minutes. This film goes the distance with Sparks, spending almost as much time on the obscure later albums as the bestsellers. As a result, the movie can feel like an endurance test.

Photo: Focus Features

But a subtle narrative flow develops over the course of The Sparks Brothers, thanks to the Maels’ admirable doggedness. Year after year, these boys keep pursuing their goals and refining their sound — whether they’re backed by a major label and scraping the lower reaches of the pop charts, or they can’t convince anyone to release their records. The back half of the doc brings a string of mini-payoffs, as Sparks keeps hopping back into the spotlight: scoring a surprise hit in Europe, playing a string of critically acclaimed shows in London, working on a high-profile movie project, and so on. The band has spent much of the 21st century thus far doing victory laps.

They’ve been making great music, too. Perhaps the real reason Wright dedicates so much time to the later Sparks albums is that those records are, for the most part, excellent. In recent years, the Maels have embraced a style influenced in part by classical music, crunching hard rock and avant-garde theater. It’s at once minimalist and maximalist: simplistic in melody and lyrics but complex in arrangements and instrumentation.

Toward the end of the documentary, the subject turns to “My Baby’s Taking Me Home,” a 2002 Sparks song that mostly consists of the title sung repeatedly for over four minutes. The hook is so catchy that it’s easy to fall under the song’s spell, until eventually the endless repetition begins to suggest some deeper meaning, which listeners feel compelled to ponder. That compulsion defines what it’s like to be a Sparks fan. And it’s a feeling The Sparks Brothers replicates, over and over.

The Sparks Brothers opens in theaters on June 18, 2021.