Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story is a fascinating “interactive documentary” from Digital Eclipse, which previously applied the same format to Atari 50, a 50th-anniversary celebration of the legendary company’s early arcade and home games. Like Atari 50, The Jeff Minter Story collects a huge range of playable, carefully emulated classic games, and puts them in context via a wealth of background material: video clips, photographs, artwork, documentation, and more, all presented via an interactive timeline. There’s one major difference: Everything in The Jeff Minter Story is essentially the work of one man.

Jeff Minter is one of the most enduring and iconoclastic figures in indie game development, a lone gunman with an inimitable style who’s been pursuing his own unique agenda — a blend of classic arcade games, trippy psychedelia, and animals belonging to the ungulate family — for over 40 years. The 61-year-old self-taught coder and designer came of age in the early-’80s homebrew computing scene in the U.K. and simply never left that way of working behind. I had the pleasure of profiling Minter last year; he’s a true character, with a perspective on almost the entire history of video game development that’s both poignant and refreshing.

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story is a great way to get to know Minter and to understand more about his work. The documentary set collects 42 games from the early part of his career, between 1981 and 1994, plus one modernized remaster by the Digital Eclipse team, Gridrunner Remastered. The best way to take it in is to explore the interactive timeline, watching the informative video clips — directed by Paul Docherty, who’s currently producing a feature documentary about Minter — and dipping into games occasionally as you go.

I, however, decided to play all 43 games back to back, in chronological order.

This is a very silly way to approach The Jeff Minter Story. It was sometimes frustrating, repetitive, and overwhelming. Minter games go very hard: brutal speed, challenging gameplay ideas, eye-watering visuals, and untethered surrealism are the norm. Also, many of the early games included are pretty crude. Nevertheless, my strange quest shone a light on both the amazing scope of what Digital Eclipse has achieved with this package, and the limitations of it.

It’s an amazing experience to watch an artist form before your eyes like this, as their preoccupations and signature quirks pop up one by one, and their design ideas are refined over time and gradually start to coalesce into a coherent whole. There are very few video game creators you could do this with, either because their work is more dissipated and collaborative, or because their games aren’t so blindingly immediate or so intensely personal.

It helps that Minter is incredibly prolific — or was, at the start of his career — and is also a shoot-from-the-hip iterator who has no qualms about working out the kinks in his ideas in public. In fact, there are a lot fewer than 43 individual games here, because Digital Eclipse includes many of the ports Minter and his friends made as they knocked out copies of his hits on new systems. Rather than cheapening the package, these illuminate both the evolving technology and Minter’s way of working. It’s interesting to see how ports of games for the Commodore VIC-20 computer to its more powerful follow-up, the Commodore 64, often seem more primitive, as Minter’s experience with the older system contrasts with him learning the ropes on the new one.

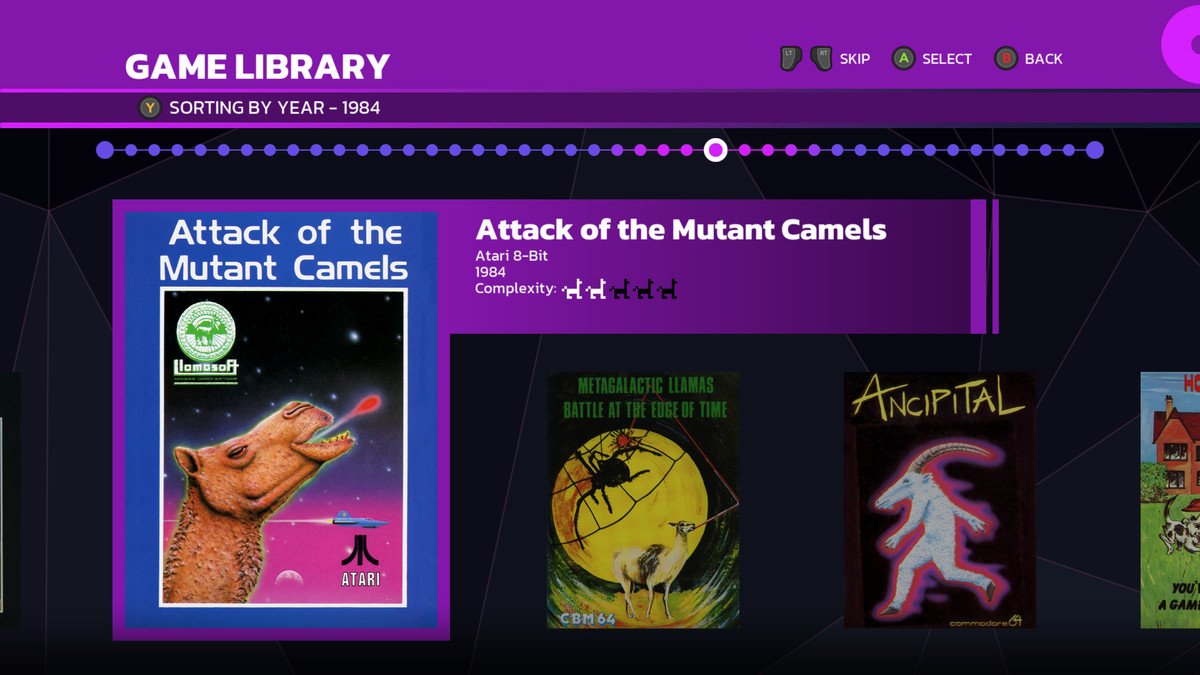

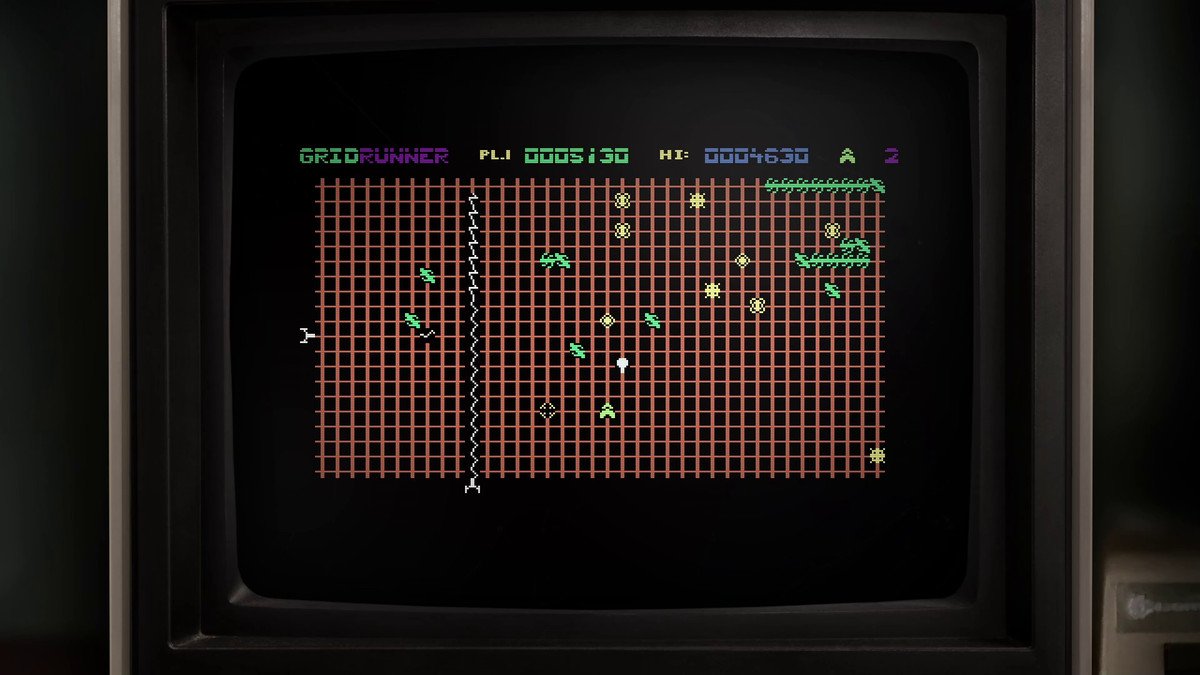

Many of his early games are unapologetic rip-offs of arcade classics like Defender and Centipede, with one or two of his own ideas inserted. (In fact, Minter’s unlicensed 1981 version of Centipede for the incredibly primitive Sinclair ZX81 computer was made without having played the original.) Sometimes those insertions are characterful goofs, like replacing the AT-ATs in an Empire Strikes Back game with camels in Attack of the Mutant Camels. Sometimes they’re diamond-hard nuggets of game design genius, like the hardened nodes that clutter and block the gameplay field in his Centipede-inspired 1982 classic, Gridrunner. Minter arguably prefigured present-day modding communities in the way he reverse-engineered his personal quirks into his favorite games.

Image: Digital Eclipse

Image: Digital Eclipse

It’s delightful to see Minter’s personality come to the fore through the games, too. First it’s his way with words: “EXCESS BAT MISERY,” proclaims simple bat-and-ball game Deflex V if you place too many bats on the field. Then surreal visual touches start to appear, like a very Monty Python hand of God that plucks the player off the screen in the almost unplayable Ratman. Strobing visual effects come next, then the games start to get much faster, and the sound intensifies. 1982’s Andes Attack begins a lifelong obsession by replacing the people in a Defender clone with llamas. There’s a satirical, parochial Englishness to the likes of 1983’s Headbanger’s Heaven and lawnmower-action game Hover Bovver.

Even better are the design ideas, devious in their simplicity, which Minter employs to mix up what’s mostly classic move-and-zap action. In 1983’s Laser Zone, the player controls two turrets on the X and Y axes of the screen simultaneously. The laser-spitting llamas of Metagalactic Llamas Battle at the Edge of Time bounce their shots off a forcefield that the player can raise or lower to control the rebounds. The action in 1984’s Sheep in Space is suspended between gravitational fields that bend shots up or down.

The issue with this collection is its truncated scope, combined with Minter’s absurd early productivity. The first 31 games in the collection cover just the years 1981 to 1984; there are 12 games from 1983 alone. It’s strongly biased toward titles that are academically interesting but that can be excruciating to play. From 1984, the narrative shifts. Minter began a strongly experimental phase that had some bizarre results, like minigame compilation Batalyx, a typically weird and unforgiving flirtation with nonlinear action-adventures called Ancipital, and the completely confounding Mama Llama. It also yielded an epiphany of sorts with Psychedelia, a gorgeous, beautifully coded light synthesizer for the C64 that would begin a lifelong love affair with light synths and music visualizers. (It’s telling that Minter spent much longer coding his light synths than his games, on average.)

Image: Digital Eclipse

Image: Digital Eclipse

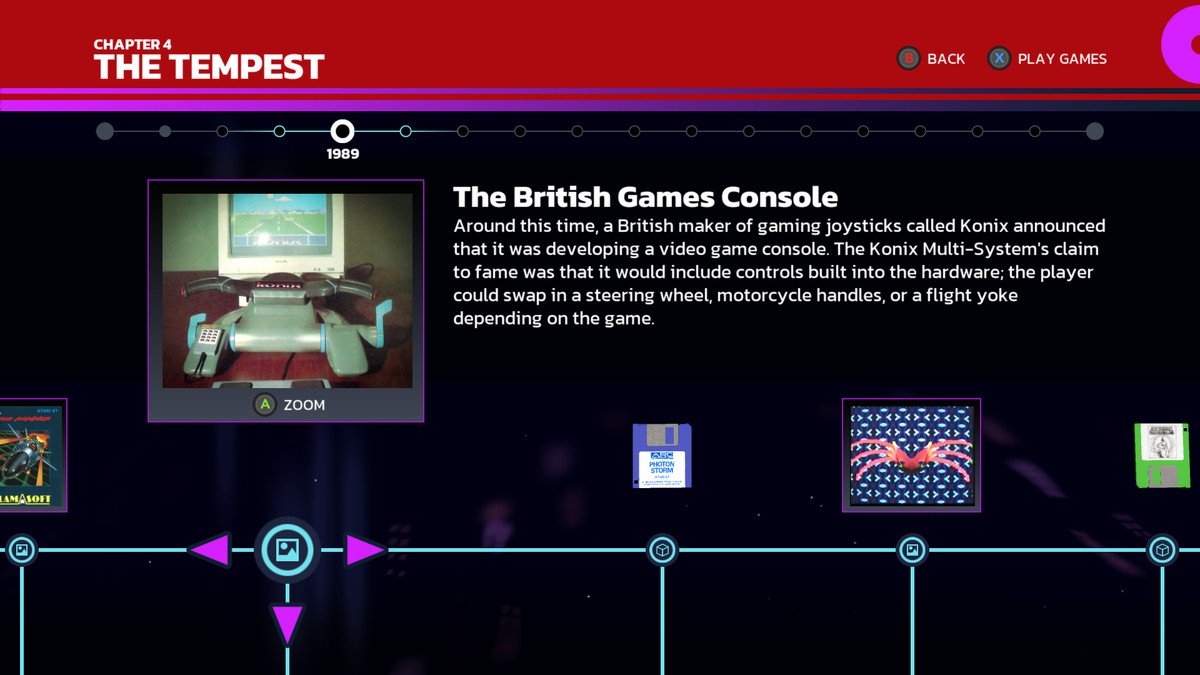

Then, after a great run of sophisticated and technically brilliant shooters for the C64 in 1986-7 (Iridis Alpha, Revenge of the Mutant Camels 2, and the mind-melting Voidrunner, which is Gridrunner with four player ships and scorching, light-synth-inspired effects), it all started to go wrong. Minter committed, as he often would, to the wrong hardware, and wasted years on a failed U.K. game console project called the Konix Multi-System (there’s an unfinished Konix game included in the Digital Eclipse collection — a super-rare curio). His pace of development radically slowed. In 1994, he made a triumphant comeback with his masterpiece, Tempest 2000 for the Atari Jaguar — which is where The Jeff Minter Story abruptly ends, arguably at the very moment Minter becomes a fully formed artist.

To an extent it’s understandable: Many of Minter’s best games from the last 30 years, including the likes of Space Giraffe and Polybius, remain commercially available on Steam and elsewhere, and presumably neither Minter nor Digital Eclipse wants to cannibalize Llamasoft’s meager sales. But it means this otherwise illuminating, funny, and exhaustively detailed portrait of a unique video game artist cuts him off in his prime.

It’s still worth checking out, though. If you do, don’t be like me and play all 43 games — play these five instead.

Gridrunner (1982)

Image: Digital Eclipse

Minter’s blinding, supercharged remix of Atari’s Centipede is undoubtedly the best game of his early years, and one he’d keep returning to again and again. The original VIC-20 version took him a week to write, start to finish.

Hellgate (1984)

Hellgate takes the two-axis shooting action of Laser Zone and cruelly mirrors it over four axes, controlled simultaneously. “The whole idea of Hellgate was in part a deliberate attempt to overwhelm,” Minter says in the collection’s documentary material, “but still to give enough control to be able to be at cause. I wanted to force entry to the ‘zone,’ the place where you go where you get so good at Robotron that you don’t really understand why, but damn, it feels good. The game feels impossible at first, but if you actually play it, then it starts to work.”

Colourspace (1985)

Minter’s evolution of his Psychedelia light synthesizer for the Atari 8-bit computer is even more mesmerizingly beautiful, with a ton of parameters to fiddle with if you want to get under the hood. Put some Pink Floyd on, grab a joystick, and peace out.

Revenge of the Mutant Camels 2 (1986)

Minter’s last game for his beloved Commodore 64 is one of his most lush and characterful, with such modern features as an upgrade store and a grid map of locations to unlock. Each level has a distinct vibe and a wild assembly of surreal enemies for your marching, leaping camel to spit at.

Tempest 2000 (1994)

Image: Digital Eclipse

Minter’s intense, techno-driven remix of the classic vector-graphic Atari arcade cab — in which enemies crawl up a 3D tube toward your craft, clinging to its outer lip — is simply one of the greatest shmups of all time. There’s something about staring down the playing field into the void that is the perfect match for his psychedelic, flow-state sensibilities.