It’s never been a better time to be Junji Ito. After a sporadic release of his work across many Western publishers in the 2000s manga bubble, the bulk of his catalogue — which, unusually for manga, largely consists of short stories and the occasional longer serial — is now readily available in fancy deluxe hardcovers from VIZ Media’s Signature imprint.

In the last three years, he’s won three Eisner Awards. Uzumaki, his longer serial about the inhabitants of a town cursed by spirals, is getting a black-and-white anime next year, set to air on Adult Swim before airing in Japan. He even had a cameo in Death Stranding (after being drafted by Hideo Kojima as a collaborator on the infamously cancelled Silent Hills).

Ito’s newest work to hit Western bookshelves, Sensor, is proof that even after all this acclaim, he’s still a master craftsman. Originally published in Japan under the title Travelogue of the Succubus and translated by Jocelyne Allen and lettered by Eric Erbes, Sensor embodies Ito’s formula of creeping dread and shocking grotesquerie, but elevates it to the level of cosmic horror. The galactic entities at the heart of this decades-spanning mystery are explained just enough to make you think twice about the night sky.

Real-life phenomenon taken to the extreme

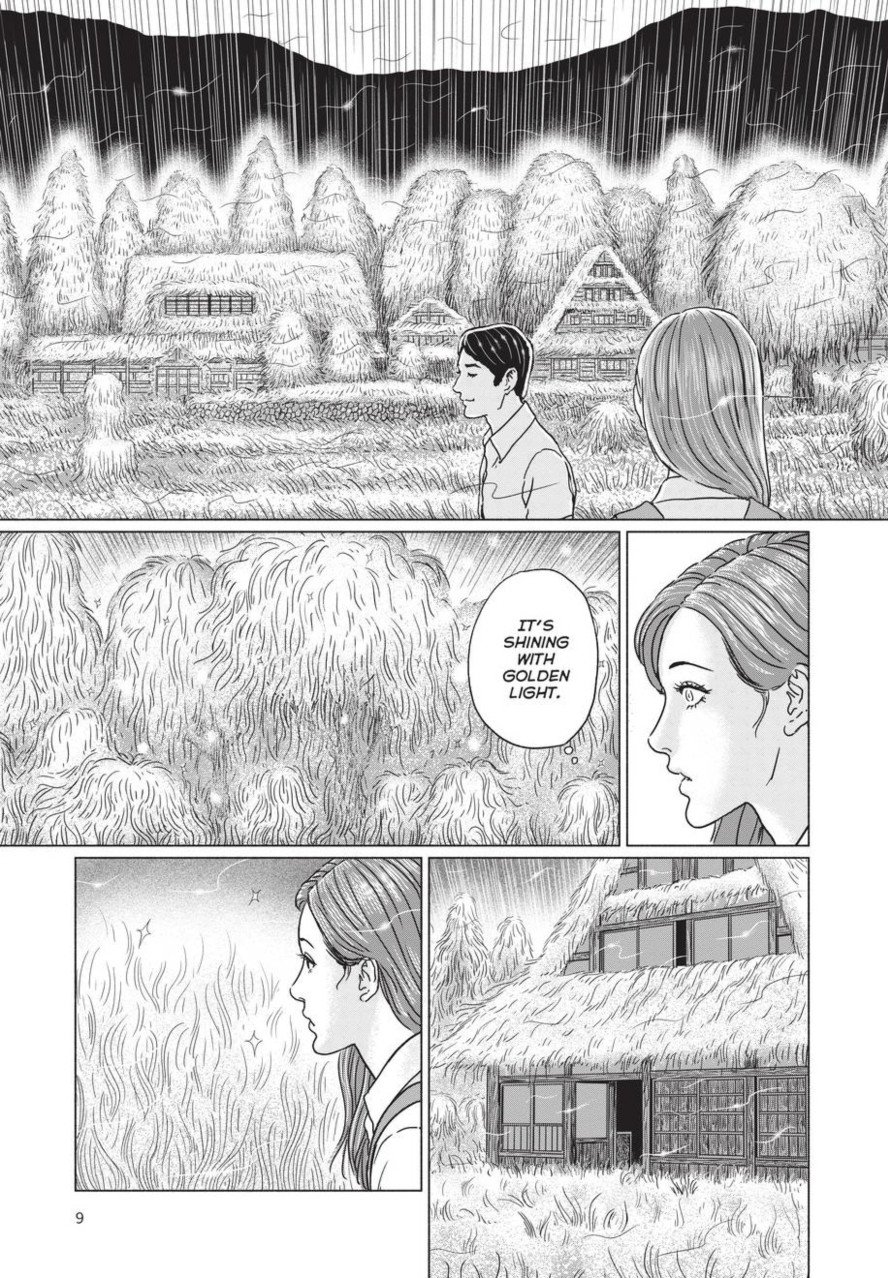

As Ito explained in a panel at this year’s Comic-Con promoting the book, Sensor was inspired when he read a book on UFOs and learned about the phenomenon known as “angel hair” — when lava from an erupting volcano cools into thin, hair-like strands and falls as strange rain. The book starts with a young woman, Kyoko Byakuya, heading to the dormant volcano Mount Sengoku simply because, as she says, “I feel I was drawn to the mountain somehow. There, she meets a man who mysteriously knows everything about her.

Image: Junji Ito/Viz Signature

He explains it’s because he’s a resident of the village of Kiyokami, which lies at the foot of the mountain and it and its inhabitants alike are coated with angel hair which, they demonstrate, gives them both telepathy and the ability to peer into the cosmos. The villagers tell the astonished Kyoko that their Edo-era ancestors harbored a Christian missionary, Miguel, centuries ago and that they and he were put to death by the Shogunate for not renouncing their faith (a period of history explored in, among other things, Martin Scorcese’s 2016 film Silence).

Ever since, the angel hair, which they call “amagami” and believe to be Miguel’s hair, doesn’t disintegrate like it does everywhere else but lingers and sticks to them and everything else. This, say the villagers, is proof that their village was chosen by Miguel, who they see as God and that, since the amagami told them Kyoko was coming, that she’s destined to bring them happiness.

Despite being creeped out, Kyoko agrees to join the villagers as they stare at the night sky, indulging in their regular, amagami-assisted ritual of peering through the cosmos to find Miguel’s divine form. But when a shower of amagami heightens their powers to incredible levels, the village winds up sensing not their Lord Miguel, but a mysterious black entity instead.

The action then cuts to 60 years later, when Mount Sengoku has erupted for the first time in decades. A team of scientists investigating the area that used to contain Kiyokami (which was destroyed in that last eruption 60 years ago) find a mysterious cocoon made out of angel hair which turns out to have kept Kyoko alive. This sets the stage for a grand conspiracy involving a reporter, Ito’s trademark body horror, a cosmic cult and, eventually, time travel … of a sort.

Unfathomable horrors of deep space

Image: Junji Ito/Viz Media

If that sounds like a lot of groundwork for a single story to cover (and one less than 10 chapters at that), it is. And some of the threads don’t always pay off — the ultimate human villain of the story is more plot point than fleshed-out character — but this is still Ito making his trademark big swings and mostly hitting it out of the park.

In particular, his artwork here is astonishing. Using spot inks and gradient effects to suggest the unfathomable horrors of deep space is an astonishing element to his bag of tricks. And his already-impressive command of facial expressions and body horror appears to have leveled up here. A repeated image of a man’s organs squeezing out of his face is at once both absurdly comical and incredibly disturbing.

All this is ably conveyed by Erbes’ lettering, which helps sell both the calm detachment and the wild frenzies characters get worked up into, and by Allen’s smooth yet suitably melodramatic translation. This team has worked on previous Ito releases before (including Remina) and they seem perfectly in sync at this point, Erbes skillfully rendering Allen’s translation with the gravity and bombast it deserves.

Is this the first Ito comic you should read if you’re new to Ito’s work? Possibly, although short story collections like Smashed or Fragments of Horror are probably an easier intro. But for the longtime Ito fan, this collection is proof that, like Stephen King, Ito just seems to improve at his chosen brand of spookiness with each new work. Here’s to many more.