The NBC sitcom Parks and Recreation had a running joke about how the fictional town of Pawnee, Indiana had a long, horrific history of violence against the also-fictional Wamapoke tribe, which lived on the land before white settlers claimed it as their own. Across seven seasons, this was little more than an aside to fill idle moments, something that gave the show’s low-stakes conflicts of local governance a meaner edge that its writers were ultimately uninterested in exploring at length. These jokes often felt like the writers’ winks to a white liberal audience, signalling their shared superficial enlightenment, which the subject of the jokes allowed to go by unchallenged. Rutherford Falls is that challenge, and it’s a pretty satisfying one.

The new sitcom is now streaming its entire 10-episode first season on Peacock. (The first three episodes are free; a subscription is needed for the rest.) It comes from Parks and Rec co-creator Mike Schur, along with Ed Helms (who also stars) and Superstore writer Sierra Teller Ornelas, who serves as showrunner. Like Parks and Rec, Rutherford Falls is a story about a small town with a complicated history, but unlike that show, it leans into that history, making comedy out of the extremely messy way it spills into the present.

Ed Helms plays Nathan Rutherford, a descendant of the town’s namesake and a staunch advocate for his family’s history. He’s super into statues and “heritage,” living in his family’s historic home, which doubles as a museum to colonial life. He’s often at odds with the local government — the show opens with what will be one of the season’s central conflicts, a statue of a founding Rutherford that is so poorly placed, drivers regularly crash into it. And he’s equally at odds with the neighboring Minishonka Nation, the indigenous community Rutherford Falls was imposed on.

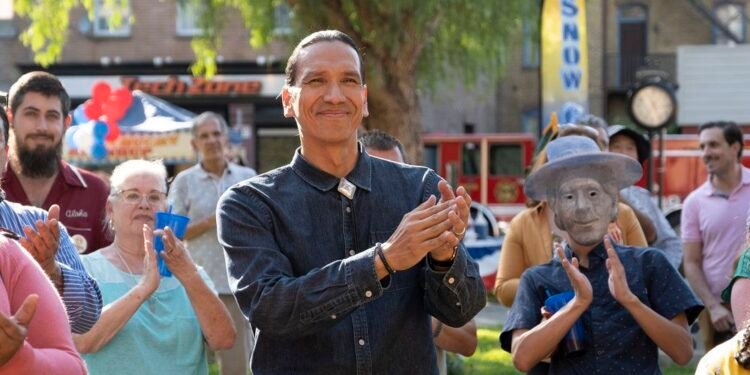

Rutherford Falls builds its world around this conflict. The mayor, Deirdre Chisenhall (Dana L. Wilson), constantly has the next election on her mind. Terry Thomas (Michael Greyeyes), the Minishonka owner of the local casino, is wholly interested in advancing his people’s cause. And Josh Carter (Dustin Milligan), an NPR reporter from Brooklyn, is in Rutherford Falls to chronicle the whole thing. In the middle of all this is Rutherford Falls’ other protagonist, Reagan Wells (Jana Schmieding), a Minishonka woman caught between two worlds as Nathan’s best friend and an aspiring advocate for her people.

Similar to other Mike Schur sitcoms, like Parks and Rec or The Good Place, Rutherford Falls is a comedy about very different people trying to work together and ultimately understand each other better. It’s lighthearted even as it deals with heavy subject matter that it’s happy to let characters talk about without a punchline. (Although one often comes.) In this, the show that it’s most like is actually Superstore, which showrunner Sierra Ornelas, who is Navajo and Mexican, previously worked on. That show also frequently examined the power dynamics of its setting.

Rutherford Falls isn’t homework, though. It’s charming as hell and often very funny, playfully unconcerned about whether viewers are in on its running jokes about, for example, the obscure Western Young Guns 2. Most of its jokes, however, are rooted in character, and its characters are refreshingly complex — everyone wants something, to the point where they behave selfishly or rashly and make things worse. It means everyone is always a little bit at odds, whether Terry is trying to force his daughter to go into business the way he did (one joke involves Terry guessing how much they can get white people to pay for her beadwork), or Reagan’s joke-fueled tension with her friends who didn’t run off to college like she did, and never let her forget it.

Colleen Hayes/Peacock

The series is at its best when it relishes the conflicts the writers set out, particularly when those conflicts involve Michael Greyeyes as Terry Thomas. He’s a comedic powerhouse who seems to just innately get the power dynamics of every scene he’s in. Thomas is laser-focused on using the power and money afforded by his business to reclaim Minnishonka land long-ago stolen by settlers, wryly yet openly hostile to the people he has to deal with in order to achieve his goals. He’s prickly toward Reagan for the way she straddles the fence between advocacy and integration, yet also supportive of her ambitions to do more for the Minishonka Nation. Terry Thomas is a brilliantly drawn character, developed enough to be the show’s protagonist, but wisely deployed in ways that make every story he’s in more interesting.

Conversely, Rutherford Falls is at its weakest when it’s leery of conflict. Its slipperiest thread is Nathan Rutherford himself, a character whose journey takes up a lion’s share of the season’s overarching story. Throughout the season, Nathan learns that he and his town aren’t what he believed them to be. So he digs in further, and is continually indulged by people he more or less constantly disrespects. Piecing together the full scope of the writers’ intentions for him is a bit maddening — he starts in a fascinating place, essentially a Parks and Recreation character adjusted just so until he becomes an antagonist — but the show is also invested in his growth.

Ironically, this decision lessens Reagan’s story, as a story about her self-actualization is continually dragged down by the dead weight of her friendship with Nathan. And given that their relationship is so central to the stories Rutherford Falls is telling, it makes it easier to notice the show’s rougher edges — like its inconsistent pacing, which robs some jokes of a fraction of their mirth, and some conversations of a bit of their bite. There’s an airiness to the affair that feels almost there, and watching it feels like rooting for your favorite team in the playoffs, only to see them go home in the semi-finals.

Colleen Hayes/Peacock

But Rutherford Falls can go home proud. It’s a series that’s trying to do a lot of ambitious and difficult things, wrestling primarily with the question of who gets their stories told, and who gets theirs ignored. Its jokes don’t just target the white opponents of its Indigenous characters, but also white allies who, under our inequitable power structures, cannot truly be considered altruistic. There’s always something to gain: social capital, a sense of pride, the absolution of white guilt — all things that do nothing for the marginalized.

Unpacking these ideas can tie ethical people up in knots, and Rutherford Falls wrestles with them through Reagan, who wants to help her community, but hasn’t been terribly involved in it. Hers is the struggle of every marginalized kid who goes off to get an education that often translates to a crash course in navigating and understanding whiteness, resulting in a degree that can help a marginalized student succeed in the world they’re graduating into, but often alienates them from the one they came from.

The show struggles with all of this on a meta level as well. Rutherford Falls boasts a large cast of Indigenous actors, writers, and musicians who all lend their talents to make the show’s fictional Minishonka Nation feel like a respectful simulacrum of their myriad experiences. And that’s remarkable, coming from within the machinery of the NBC sitcom empire, which has historically been defined by white voices speaking to white audiences, and elevated by white critics. (Two of which — Schur and Helms — lend their names in order to entice said white audiences into showing up for a story that isn’t about them.) But Rutherford Falls also makes this part of the joke: It’s clear-eyed about the game that’s being played, and it’s going to make sure its people get paid.

Season 1 of Rutherford Falls is now streaming on Peacock.