Making one of the better Hellraiser movies isn’t all that difficult, to be completely honest. Any franchise with more than three or four entries is bound to be uneven, but Hellraiser’s drop-off is particularly sharp, going from a sequel that improves on the original (Hellbound: Hellraiser II) to two movies that aren’t good, exactly, but are quite fun to watch (Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth and Hellraiser: Bloodline) to a long run of direct-to-video sequels so bad, the series starts to look like a meta-joke where pain is being inflicted on the audience instead of the characters. And yet, for nearly 35 years, fans have remained devoted to 1987’s Hellraiser and Clive Barker’s diabolical vision.

Director David Bruckner is one of those fans. That’s clear watching his new reboot of Hellraiser, which doesn’t go back to the source material, exactly, but does remain loyal to its spirit. The heroes of this straight-to-Hulu film are dirtbags, queers, and addicts. The tone of the movie is very serious and adult, a welcome pivot from teen-centric slashers like Scream (2022) and Bodies Bodies Bodies. The occult art deco production design blows the original’s puzzle box up to awesome architectural size. The Cenobites inspire a breathtaking combination of wonder and terror, soft-spoken and luminescent under the pale moonlight. And the chains… oh yes, there are chains, flying in every direction and ripping human bodies apart like bags of milk.

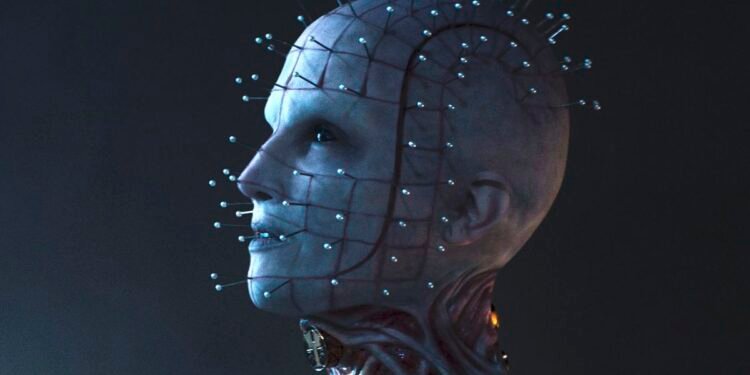

Still, Bruckner’s priorities, and those of screenwriters Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski (The Night House), are somewhat different. While the 2022 movie has an omnivorous sexuality that feels right for Hellraiser — we see both gay and straight couples naked in bed together, and there’s more male nudity than female — this version is less kinky than Barker’s sadomasochistic original. In that film, the promise of an eternity spent on the knife’s edge between pleasure and pain held a perverse fascination. Here, it’s an unequivocal evil, with no appeal for anyone except for the Cenobite leader, billed here as The Priest (Jamie Clayton), and her minions. Even Hellraiser’s depraved billionaire (and there simply must be a depraved billionaire) regrets his adventures “in the further regions of experience.”

Photo: Spyglass Media Group/Hulu

Instead, Bruckner and company get off on franchise lore. This film fleshes out the world of the Cenobites in new and comprehensive ways, laying out exactly how the Lament Configuration (i.e., the puzzle that summons the Cenobites) works and the seven steps a penitent must go through in order to request, as the film puts it, “an audience with God.” Each of these steps requires a human sacrifice, and Hellraiser buys itself time by having its protagonist figure this out and deliberately draw out the intervals between these bloody offerings. It’s here that the film starts to lose focus.

Hellraiser opens with a title card that reads “Belgrade, Serbia,” which replaces Morocco as the global capital of taboo delights. There, the Lament Configuration is purchased and brought back to Voight (Goran Višnjić), the decadent billionaire referenced above, who promptly sacrifices a young man to it and summons the god Leviathan. Fast-forward six years, and the box sits abandoned in a shipping container in an empty warehouse. Then 20-something degenerates Riley (Odessa A’zion) and Trevor (Drew Starkey) “liberate” it while searching for valuables they can sell for quick cash.

The couple met at a 12-step meeting, but simply handling the box pushes recovering addict Riley off the wagon. Here, Bruckner’s film reaches for a more realistic tone, placing the Hellraiser universe in something that more closely resembles our world than anything in Barker’s original. The subsequent argument between Riley and her more responsible brother Matt (Brandon Flynn) similarly grounds the film in down-to-earth conflicts and settings — until the arrival of the Cenobites turns a public park into a surreal nightmare, and Matt inexplicably vanishes.

Overwhelmed by guilt and grief, Riley goes out searching for clues about the puzzle box she suspects might have caused Matt’s disappearance, briefly launching the film into a procedural plot it should have followed through to the end. Instead, it shifts focus once Riley breaks into Voight’s Massachusetts mansion, with Matt’s boyfriend Colin (Adam Faison) and their roommate Nora (Aoife Hinds) following close behind. There, Hellraiser pivots from a mystery into a siege film, as the group barricades themselves inside Voight’s palatial home while the Cenobites gather outside.

Photo: Spyglass Media Group/Hulu

This chunk of the film highlights Hellraiser’s two biggest weaknesses: the characters and the length. The film earns most of its two-hour running time, but Riley bringing the rest of the gang up to speed on what the hell those things are and what they want burdens Bruckner’s reimagining with a few too many dialogue scenes during an already slow stretch of the film. And aside from the fact that she has a brother and a weakness for booze and pills, we know relatively little about Riley. We know even less about her friends — a moment of silence, please, for poor Nora, who has no distinguishable character traits except for being “the roommate.” That makes it difficult to engage with the drama between the characters, about which even the film’s writers seem indifferent.

Perhaps appropriately, the most compelling figure in the film is a Cenobite. Of the five actors who have put their mark on the infernal bureaucrat colloquially known as Pinhead, Jamie Clayton is the only one besides Doug Bradley to really embrace “Pinhead” as a character. Clayton’s version is breathier and more feminine than Bradley’s authoritative priest figure; she’s more of a holy mystic than a pope-king. Her black eyes look at the humans begging for mercy in front of her with the cold curiosity of an alien scientist, and she waits patiently for them to come to her with regal posture and delicately folded hands. Clayton’s Pinhead is a different, quieter type of frightening, which makes the voluminous dialogue she delivers in the film (far more than Bradley in the 1987 movie) rather ironic.

The Cenobite design in Hellraiser is excellent all around, taking advantage of advancements in prosthetics to scrap black leather fetish gear in favor of suits made out of their own flayed skin. Familiar characteristics are exaggerated — the female Cenobite’s throat folds have never looked so vaginal — and new designs evoke the horror of iron lungs, cleft hands, and human taxidermy. The film is bloody and intense when it needs to be, at one point following a pin through a character’s throat and out the other side. But its most inventive horror flourish is built into the sets, which shift and clank into place like the pieces of the Lament Configuration when the Cenobites are near.

Hellraiser 2022 easily clears the admittedly low bar of being one of the best Hellraiser movies. It’s the best one since Hellbound: Hellraiser II, and might even be the second best in the series after that film. It has some great, grotesque visuals, which makes it a real shame that this film isn’t getting a theatrical release. And it accomplishes what many fans (including this one) wanted for the series, which was to pull it out of the creative purgatory where it’s been stuck for a couple of decades now. The only thing to fret about at this point are the points where Barker’s kinky edge has been sanded down for a more sex-averse era, and his enigmatic storytelling scrapped in favor of exposition that’s more legible, but less compelling. Beyond that, the suffering is exquisite.

Hellraiser will be released on Hulu on Oct. 7.