Detlef Koschny • September 27, 2019

Defending our planet from the hazard of potential asteroid impacts requires investments from the whole world. In Europe, the European Space Agency (ESA) works to study asteroids and mitigate the near-Earth object impact threat in several programs, and the European Union (EU) supports some programs as well.

ESA is working with other nations to track, characterize, and potentially deflect hazardous near-Earth asteroids. ESA is chairing the United Nations-mandated Space Missions Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG) and is participating in the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN). For these activities, ESA has invested 3 to 10 million euros per year since 2009.

Within the Space Situational Awareness program, active since January 2009, ESA is supporting work to understand the hazards represented by near-Earth asteroids. ESA is currently performing follow-up observations of known objects and is also developing a 1-meter-class wide-field survey telescope to find new objects. They are maintaining and developing software to perform orbit computations and impact-monitoring activities. The Near-Earth Objects Dynamic Site (NEODyS) system, developed by the University of Pisa in Italy, is being updated and moved to the ESA center in Frascati, ESRIN, to perform these tasks.

Planetary Defense

The Planetary Society is working to decrease the risk of Earth being hit by an asteroid or comet.

ESA performed studies for future asteroid sample missions under the name of Marco Polo and MarcoPolo-R. Each of these studies had a budget of about 1.6 million euros, coming from ESA’s General Studies Programme. Neither is proceeding toward development, but recently, ESA selected the Comet Interceptor as its first F-class mission. (F-class missions are small, with a mass under 1,000 kilograms, and have a relatively fast development timeline.) Cost-capped at 150 million euros, Comet Interceptor will go to one of the Lagrange points and wait for a newly discovered comet (or maybe even an interstellar asteroid, like `Oumuamua) to come within Comet Interceptor’s flight range.

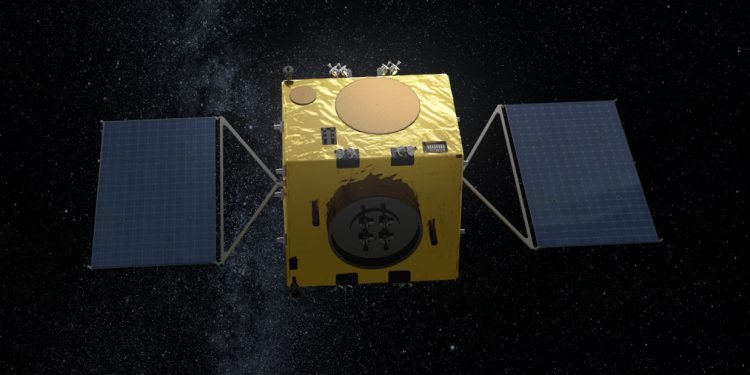

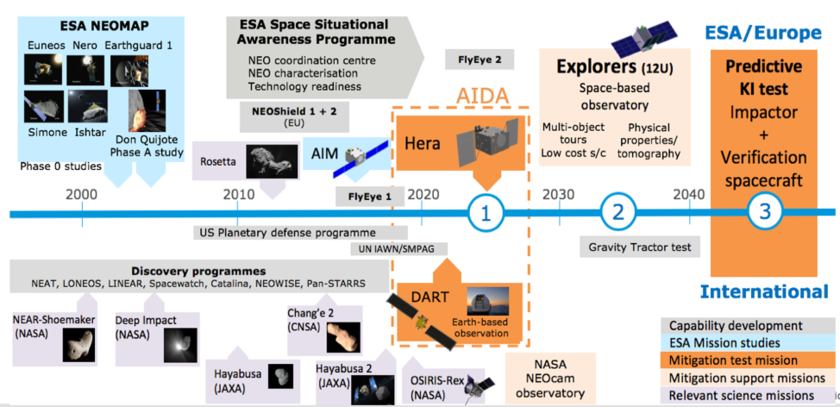

Within the General Studies Programme, ESA is also considering a contribution to the NASA-funded AIDA mission to demonstrate the deflection of an asteroid. The U.S. part, called DART (Double-Asteroid Redirection Test) will impact the secondary of the binary asteroid Didymos. ESA may follow up with the Hera mission, which would arrive at Didymos in 2024, 2 years after the DART impact, and characterize the system in detail. ESA has already spent several million euros to study this mission. The figure below shows how Hera and other European planetary defense activities would fit within an international roadmap.

Since fall 2018, ESA’s NEO-related activities are managed mainly by a core team of 10 people within its Planetary Defence Office. The office is currently preparing a funding request for the next ESA ministerial council meeting, which will take place in November of this year. In the area of near-Earth objects, they are requesting a continuation of the funding of the ongoing Space Situational Awareness activities, plus 230 million euros for the implementation of the proposed Hera mission. Both of these projects will then fall under the new so-called Space Safety Programme, together with activities in the areas of space weather and space debris.

For its part, the EU has invested several million euros in the NEOShield and NEOShield-2 programs, which support a variety of planetary defense activities such as the development of asteroid-deflection scenarios and astronomical observations. For the coming years, the European Union has allocated 6 million euros for an activity called “Advanced research in near Earth Objects (NEOs) and new payload technologies for planetary defence“, part of Horizon 2020, a European Union program intended to stimulate technology research and development.

The work of the European Union and that of ESA has been complementary, with the EU work focused on asteroid deflection and physical-properties observations and ESA providing ground-based position observations, data archiving, survey telescope construction, and mission implementation. It is expected that this work will continue on a similar—and hopefully increasing—level over the next few years.